I can safely say without hyperbole that there has never been a filmmaker quite like Satoshi Kon. Although he only managed to direct four feature films in his lifetime, all of them are considered masterpieces of animation and are marked by his fascination with surrealism.

Blurring the line between reality and fantasy, Kon’s characters easily confuse one for the other and become lost. His works (particularly his first and last projects) show a keen insight into the effect the internet would have on our psyches, with his predictions coming to pass in startling and horrific ways.

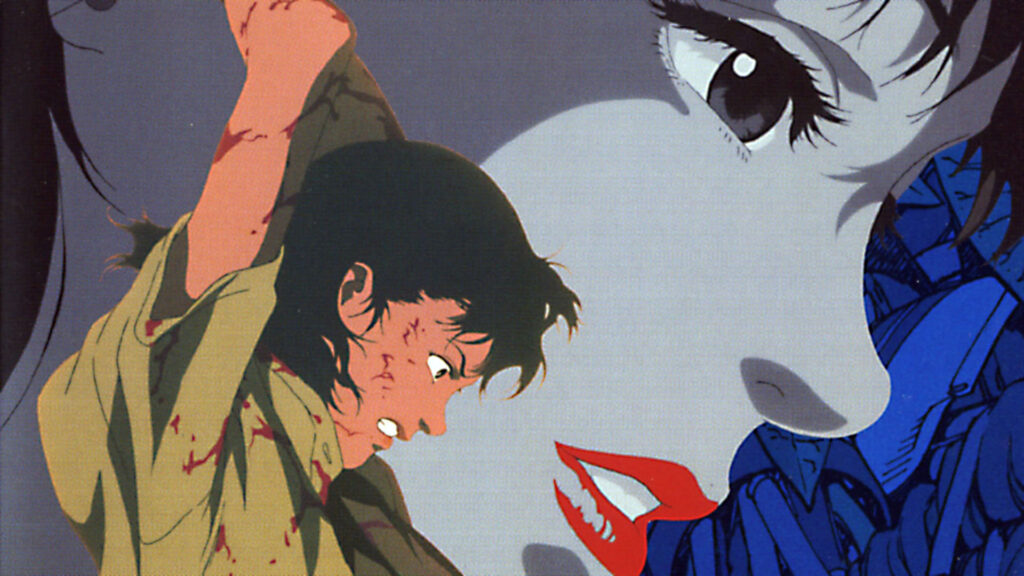

Kon made his directorial debut with the psychological thriller “Perfect Blue” (1997). Loosely based on a novel by Yoshikazu Takeuchi, the film follows Mima Kirigoe, a pop idol who announces she’s quitting the music industry and pursuing a career in acting, shedding her clean-cut image in the process.

This decision upsets Mima’s obsessive fans, one of whom launches a website reporting on her daily activities in the first person as “the real Mima.” Along with the difficulties of her new job, being stalked pushes Mima to the brink of a psychotic break—amid a series of brutal murders, no less.

You may be thinking, “Gosh, that sounds a lot like Darren Aronofsky’s ‘Black Swan.’” And you’re not far off. Although Aronofsky denies being inspired by “Perfect Blue,” he has acknowledged the similarities between the two films and shown appreciation for Kon’s work (Kon, in turn, was said to have been a fan of Aronofsky’s “Requiem for a Dream”).

Still, Kon’s talents as an author of speculative fiction sets the two films apart. The cyberstalking and harassment Mima experiences have become epidemic on social media, thanks in no small part to platforms like YouTube and Twitter profiting off any engagement at any price, regardless of the harm it does.

(No, I’m not calling Twitter “X”. If Elon’s gonna deadname his daughter, I’m gonna deadname his shitty racist website.)

“Perfect Blue” also came out one year before the Clinton-Lewinsky Scandal turned a 23-year-old intern into a national punching bag, preceding targets like Dylan Mulvaney, Imane Khelif, and any actress who’s been featured in a “Star Wars” project. Thirty years onwards, Mima’s struggles are still an all-too-real hazard of life in the digital age.

The dangers of a computerized existence persist in “Paprika” (2006), which is Kon’s most ambitious work and a dire warning about our interconnected future (and, sadly, his final film). Based on the novel by Yasutaka Tsutsui, “Paprika” reveals a world where humans wield the technology to monitor people’s dreams—and a new invention, the DC Mini, that allows scientists to enter and affect them.

One such person is psychiatrist Atsuko Chiba, who uses the DC Mini to treat her patients under her alter-ego, the fabulous dream detective Paprika. The plot kicks off when prototypes of the device are stolen, threatening the collective subconscious of all Tokyo.

You may be thinking, “Gosh, that sounds a lot like Christopher Nolan’s ‘Inception.’” And you’re not far off. Both are films that deal with layers of illusion and unreliable narrators, all while using the feat of influencing dreams as a metaphor for filmmaking.

That said, Nolan’s dreamworld is linear and literal, while Kon’s is bright, whimsical, and chaotic. So chaotic that during the climax of “Paprika,” a “rogue dream” breaks into the real world, unleashing havoc and destruction.

Beneath the film’s parade of marching furniture and singing Buddhas, Kon once again probes the depths of cyberspace (Paprika says that the internet and dreams are alike, speaking of “conscious mind vents”). The film’s ultimate fear is that the extreme emotions stoked by the internet will invade our world—a prophecy that came to fruition, as anyone who has lived through the past decade can attest.

Though Kon died of pancreatic cancer at age 46 in 2010 (while developing his fifth feature), he is remembered as an auteur of anime and as one of cinema’s great seers, having predicted the unholy collision of fascism and technology that took root after his death.

In no small part due to bad actors gaming social media algorithms, Donald Trump and the Make America Great Again movement have stuck around, injecting American politics with the vicious tactics of Gamergate (the misogynistic smear campaign against journalist Anita Sarkeesian and video game developers Zoë Quinn and Brianna Wu).

At first, MAGA’s digital machinations seemed to peak during the January 6th insurrection, egged on by Facebook’s proliferation of conspiracy nonsense. Yet Trump’s second term took off what few guardrails remained, leading to an administration run by the worst dregs of the World Wide Web.

In this digital dystopia, antivax weirdos, crypto scammers, AI cultists, and outright Nazis run the show. It’s not for nothing that the organization created to demolish the federal government was named after a fucking meme.

Satoshi Kon foresaw the damage the internet could cause if not properly checked, but he also knew humanity could transcend its toxic influence. That’s why Kon’s movies embrace hopeful endings—and why, 15 years after his passing, Kon’s work remains worthy of study and celebration.