After shattering the world record for unmemorable performances in passionless blockbusters, Dwayne Johnson has surrendered himself to “The Smashing Machine,” becoming a massive chunk of clay in the twitchy hands of Benny Safdie (who directed this mixed martial arts biopic).

To be clear, this is not Johnson’s first good performance (much respect to his pious bodybuilder in “Pain & Gain” and his fatally overconfident cop “The Other Guys”). It is, however, the first time he has allowed himself to appear human onscreen.

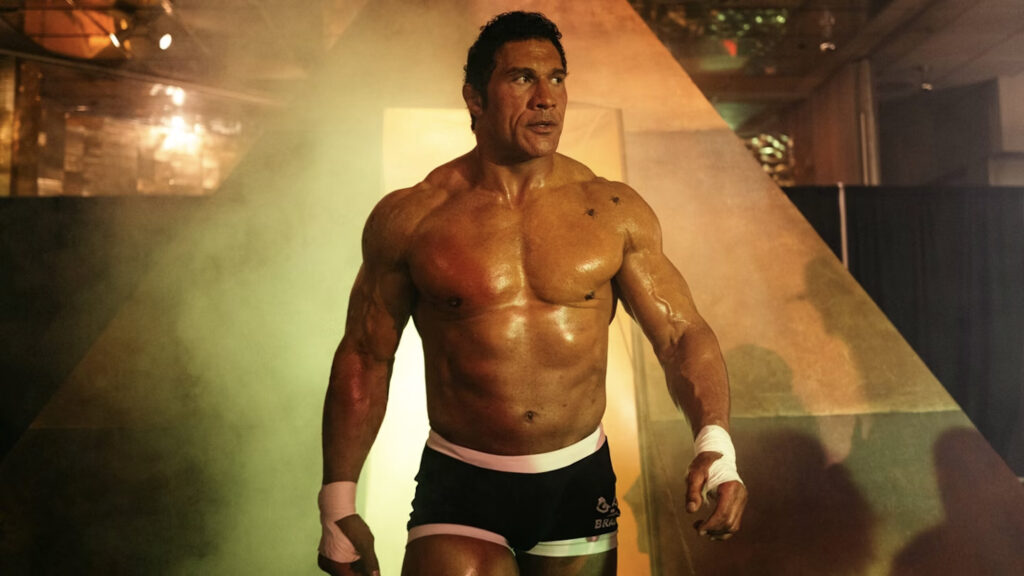

In portraying MMA pioneer/canary in the coal mine Mark Kerr, Johnson lets himself look awkward: spaced-out, humbled, too big to comfortably ride an escalator, and too fragile to win an argument with his volatile girlfriend Dawn (Emily Blunt). You can see why Johnson cried during the film’s 15-minute standing ovation at the Venice Film Festival; at long last, he’s vulnerable.

Whether Benny Safdie (directing his first film without brother Josh) knows exactly what to do with that vulnerability is another question. He certainly probes it stylistically by shooting the seminal years of Kerr’s MMA career (1997 to 2000) in verité documentary style—an approach that isn’t always involving or exciting, but holds a magnifying glass up to the contradictions of Kerr.

Yes, Mark’s traps bulge so dramatically they look like they might scale his neck and plant a flag on his head. But he’s soft-spoken, exceedingly polite, and overly deferential to everyone who would seek to exploit him.

“The Smashing Machine” begins with Mark as a burgeoning star in the earliest days of the Ultimate Fighting Championship (though most of the action takes place in Japan’s rival promotion, PRIDE). He’s a national champion wrestler trying to find his way in an MMA landscape filled with specialists—strikers, grapplers—not the multi-tool fighters that dominate MMA today.

As seen in the opening montage, Mark succeeds mostly on his raw power, which is hardly a challenge for Johnson to play. Honestly, his biggest acting feat in the fight scenes is pretending to be only 6’1”.

The combat scenes might actually be too easy for Johnson (who became a global icon by, ya know, pretending to fight). These bouts aren’t particularly brutal or stylized; they’re just faithful recreations of existing documentary footage (the film is based on the 2002 documentary “The Smashing Machine: The Life and Times of Extreme Fighter Mark Kerr”).

Instead, Safdie saves most of his interesting choices for outside the ring, revealing Mark simultaneously at his peak and in freefall from painkiller addiction, which creates an oblique narrative vantage on the world’s oldest sports arc: athlete falls on hard times, seeks his purpose, attempts a comeback.

As a behavioral study, juxtaposing success with dry rot is the movie’s best punch. Mark earnestly humors reporters about what it might feel like to lose (he can’t really imagine!), yet we see him weaponize the same charm to hide his opioid abuse from pharmacists and insurance companies.

That Mark is doped up from the moment we meet him leads to one of Safdie’s most interesting directorial flourishes: The first half of “The Smashing Machine” is sound-designed completely differently from the second half.

We can only assume that this is because Mark is high, causing punches to sound muffled when they land (like microwave popcorn bursting two rooms away). Compare that to the film’s climactic tournament, during which the cacophony of the ring is sharper and harsher, suggesting the sensory difficulties of being sober in an insane sports environment after years of self-numbing.

Safdie is also keenly interested in the weirdness of MMA’s wild, unregulated infancy. That includes a press conference where PRIDE formally announces “please, no eye-gouging or biting anymore” and a funny moment when real-life heavyweight boxing champion Oleksander Usyk (here playing mixed martial artist Igor Vovchanchyn) tries to clarify what kinds of knee strikes to a downed opponent’s skull might still be allowed.

(Far less intriguing is the manufactured drama around whether Kerr will be forced to fight his dear friend Mark Coleman, played by another real-life fighter, Ryan Bader, in a PRIDE tourney.)

While “The Smashing Machine” possesses little of the raw intensity of Sadie Bros breakouts “Uncut Gems” (2019) and “Good Time” (2017), composer and harpist Nala Sinephro does produce a score that could only be called “stress jazz,” with drum solos running underneath several minutes of fighting.

The music is more evidence of Safdie wanting to approach a traditional tale from an uneven keel, but he never figures out how to make MMA itself interesting. The fights lack the choreography of the best boxing movies or the clean, concussive theater of punches landing. Many of Mark’s wins and losses appear the same. They just…end…with someone pinned or tapping out, their face barely visible.

The strangest sports telecast flourish is that the ringside commentary is mixed ambiently in the film, as though it were being narrated from inside Mark’s head. But that’s a dissonant choice given that the fight POV is extremely third-person and not from his perspective at all.

For her part, Emily Blunt fiercely crashes into the ceiling of another “biopic significant other” role as Dawn and Mark’s see-saw relationship produces the best fights in the film. Their arguments are rhythmic dances—unpredictable, pathetic, funny, and scary.

In one moment, Mark is pruning a cactus in their backyard because he’s newly sober and badly needs a hobby; in another, he’s about to throw a plate in frustration, but instead elbows a door into oblivion, because the Rock has to pick on something his own size.

Despite that physical outburst, Dawn is better at arguing than Mark. She’s sharp-tongued and far more elusive, always in a fallible dance of trying to support him, while feeling burdened by his addiction—not to mention not-so-secretly liking him better when he was a high-functioning addict.

At no point does everyone’s favorite “Jungle Cruise” (2021) couple convincingly have the hots for each other, but Blunt (who’s been perfecting sarcastic glares since “The Devil Wears Prada”) brings out the best in her scene partner by belittling him, letting us all watch how Johnson handles unknown (to him) emotional terrain.

Perhaps Johnson and his character learned the same lesson over the course of “The Smashing Machine”: Losing can be liberating.