In an emotionally piercing scene from Bryan Singer’s “X-Men” (2000), Rogue (Anna Paquin) stares at Logan, a.k.a. Wolverine (Hugh Jackman), her eyes fixing on the battered skin that conceals his claws. “When they come out, does it hurt?” she asks.

Absorbing the silence that follows, you half expect the stoic Logan to squint, growl, and berate Rogue for implying that anything could hurt him. Instead, he pauses, then bracingly answers with the truth: “Every time.”

Twenty-five years ago, those words seemed to encapsulate the film’s sincerity, humanity, and gravity. Today, however, they are a reminder of a nauseating truth: that the hurt of “X-Men” cuts far deeper than Logan’s claws.

Credited with (or blamed for) unleashing the post-9/11, pre-pandemic tidal wave of comic book movies, “X-Men” and its titular mutant superheroes were square one for the super-humanist spirit that reshaped the genre. (Before: Joel Schumacher’s “Batman & Robin.” After: Christopher Nolan’s “Batman Begins.”)

“Singer’s 2000 movie [was] the catalyst for everything seriously superheroic that’s come since, good and bad,” Chris Hewitt wrote in Empire in 2014. “Without it, there’s no Marvel Studios.” (Kevin Feige, the current president of Marvel Studios, was an assistant to “X-Men” producer Lauren Shuler Donner.)

Though I concur with Hewitt, “X-Men” was always more than a mere catalyst to me. I first saw the film when I was 15 years old—and swiftly became enraptured by the darkly poetic imagery and soulful seriousness that defines Singer’s filmography.

“Ladies and gentleman, we are now seeing the beginnings of another stage of human evolution,” Dr. Jean Grey (Famke Janssen) declares early in the film. At the time, I was undergoing an evolution of my own: the formative experience of becoming a movie buff who chased directors across franchises, genres, and years.

“As a kid watching films, you go through a gradual realization of what’s behind them,” Christopher Nolan told DGA Quarterly in 2012. “So when I was young and looking at ‘Alien’ and ‘Blade Runner,’ I was going, ‘Okay, they’re different stories, different settings…but there’s a very strong connection between those two films, and that is the director, Ridley Scott.’”

There was a time when I thought that my Ridley Scott was Bryan Singer—a time when I eagerly followed him from the alluring shadows of “The Usual Suspects” (1995) to the endless skies of “Superman Returns” (2006), blithely unaware of the speculation surrounding his personal life.

That changed in 2014, when I saw a Hollywood Reporter headline that slammed straight into the forward rush of my fandom: “Director Bryan Singer Accused of Sexually Abusing 17-Year-Old Boy in 1999.”

At the time, I was locked into the cultish mindset of auteur worship (a state that became easy to settle into once the accuser, Michael F. Egan III, withdrew his claims and was sentenced to two years in prison for investment fraud).

In 2019, however, further ignorance became impossible when The Atlantic published an article chronicling Singer’s alleged history of abuse—based on interviews with additional accusers like Cesar Sanchez-Guzman and Victor Valdovinos, as well as anonymous sources.

(A preemptive post to Singer’s Instagram account called the piece, which was written by Alex French and Maximillian Potter, an “attempt to rehash false accusations and bogus lawsuits.”)

The Atlantic article, which includes allegations that predate “X-Men,” didn’t just spur Singer’s exile from Hollywood; it gave past colleagues latitude to speak about him in brutal terms. (Or, in the case of Rami Malek, Singer’s Oscar-winning “Bohemian Rhapsody” star, sheepishly ask, Bryan who?)

As revealing interviews percolated, the production of “X-Men” came into clearer focus, revealing a Singer unknown to students of either fawning publicity or dauntless exposés: an artist as vain as he was inventive, as vindictive as he was imaginative.

To fill out that portrait with a few more brushstrokes, I decided to mark the film’s 25th anniversary by reconstructing its chaotic origin, consulting more than 30 accounts (including articles, books, and podcasts) and placing them in conversation with each other. (For a complete bibliography of sources, please see the end of this article.)

In the past, “X-Men” has been reduced to dishy anecdotes (like Michael Jackson’s peculiar interest in playing Patrick Stewart’s character, Professor Charles Xavier). The following oral history provides a more detailed and nuanced account of the interpersonal clashes and impulsive creative choices that made up the film’s genetic material, birthing a fraught genre masterpiece.

Telling that story was an uneasy undertaking. Imbibing the grudges and grievances of the people who made “X-Men,” I remembered the sly exchange that concludes David Fincher’s “The Social Network” (2010), which undermines the very notion of an accurate recollection.

“When there’s emotional testimony, I assume that 85 percent of it is exaggeration,” Marylin Delpy (Rashida Jones) informs Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg). “And the other 15?” he asks. “Perjury,” she says flatly. “Creation myths need a devil.”

I can’t tell you which percentage of what follows is emotional testimony and which is perjury; I wasn’t present when “X-Men” was made. Yet I played a part in the film’s surreal odyssey: the part of an ardent fan struggling to reconcile my adoration of Singer’s artistry with our post-Me Too reality.

(It is equally true that Singer is innocent until proven guilty and that the reporting of French and Potter is worthy of serious consideration.)

Since the start of the Me Too movement, many cinephiles have prayed to the false god of “separating the art from the artist.” I believe that the artist is the art, which means that we must choose between remaining in perpetual denial, avoiding directors we deem dishonorable, or continuing to watch their work and living with some deep discomfort.

As a writer, my job isn’t to tell you which choice to make; it’s to share knowledge that helps you choose. Just know that whatever choice you make, it will hurt. Every time.

The Origin

Bryan Singer’s breakout film was “The Usual Suspects,” which earned a Best Original Screenplay Oscar for screenwriter Christopher McQuarrie (who grew up with Singer in Princeton Junction, New Jersey). Yet it was “Public Access” (1993), an intimate thriller about a malevolent television host (the late Ron Marquette), that put Singer on the path to direct “X-Men.”

Christopher McQuarrie: I was working for a detective agency in New Jersey. These people [from a Japanese corporation] approached Bryan and asked him to do this film. He had been watching public-access television the night before, which was kind of a new thing, and he found it fascinating. They said, “What’s your next project?” and he said, “‘Public Access’!” And he made up the plot of the movie on the spot. [1]

Bryan Singer: I used to do magic when I was a kid. With film, the whole notion of persistence of vision and manipulation…there’s a kind of magic going on. [In “Public Access”] a stranger comes to a small town and the town becomes very enamored with him—and they don’t realize that beneath the surface, he has his own agenda that’s very disorienting and confusing. He could be an alien or a murderer from the city. [2]

Christopher McQuarrie: [Bryan] called me in New Jersey, and I had run my course at this detective agency and had applied to the New York Police Department—with another friend of Bryan and mine that we grew up with. We had the idea that we were going to join the NYPD as kind of a gag. Bryan called and said, “Do you want to write [‘Public Access’]?” I was thinking about it: Getting shot, writing for Bryan…you really do have to think about that. [1]

Bryan Singer: It’s a real challenge [working in confined spaces], especially with two characters. It’s odd that I should do “Public Access,” where 30 percent of the movie takes place with one guy in the public-access cable station. Then, in “The Usual Suspects,” the same amount of the movie takes place with two guys in an interrogation room. [3]

Despite splitting the Grand Jury Prize for best dramatic feature at the 1993 Sundance Film Festival with “Ruby in Paradise,” “Public Access” never received a theatrical release. However, the film had a high-profile fan: Peter Rice, a young British executive at Twentieth Century Fox.

Peter Rice: I saw “Public Access” and I thought it was an astonishing film by a young, first-time filmmaker. That was kind of my schtick at the time: I’d get to go to film festivals. I met this whole generation of new storytellers, and invariably, I could be the first person from a major studio to say, “I liked your stuff.” [4]

Christoper McQuarrie: I do not mean this to insult anybody involved in the production, [but] I find “Public Access” to be an objectively terrible movie. Considering how much it was made for, there’s some fairly inventive filmmaking, but it’s a mess of a movie. [5]

Peter Rice: At that time, in order to try and reach somebody, they had these little mailboxes in the main part of [Sundance]. So I remember writing some really flattering letter to Bryan and putting it in his mailbox to see if he’d call me back or find me. [4]

Bryan Singer: I was so nervous and excited to go onto the Twentieth Century Fox lot, and I met with Peter, who was a junior executive. [He had] a cool office, nicer than my dad’s, but it was still quite a narrow office, as I remember it. I thought Peter was quite adorable and had an adorable accent, and yet there was nothing else in the office except a little picture on the wall from “Miller’s Crossing.” I just remember saying, “Oh, ‘Miller’s Crossing.’ You like the Coen Brothers.” What felt like a formal meeting [became] a conversation with someone I could get to know as a person. [4]

Peter Rice: I was always looking for things to work with Bryan on. That started with “X-Men,” which was a few years later, after he’d made “The Usual Suspects.” [4]

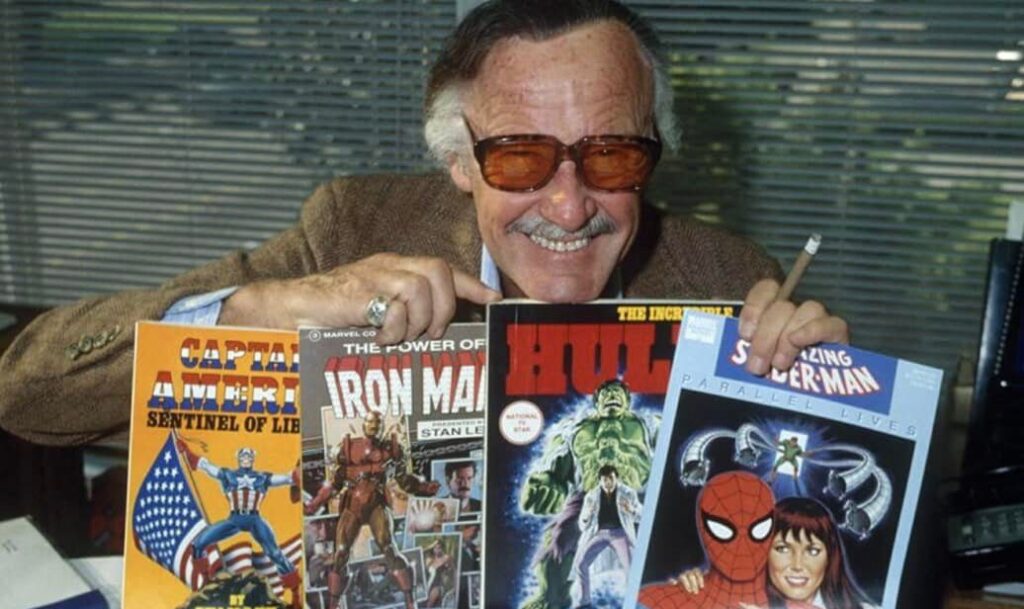

In 1996, Fox hired Singer to direct “X-Men.” Despite being unfamiliar with the source material, Singer was charmed by the co-creator of the mutants: Marvel Comics godfather Stan Lee (who died in 2018).

Bryan Singer: I didn’t know the comic and there was a script that was written that was a bit post-apocalyptic, weird. I didn’t quite connect to it. But I sat down and I studied the character histories and I met with Stan Lee—and he was so cool to me. He treated me like I was a god. [6]

Stan Lee: Bryan Singer and [“Spider-Man” director Sam Raimi] are at opposite ends of the pole. Sam is a big comic book fan, especially “Spider-Man.” Bryan had never been a comic book fan, and he hardly knew who the X-Men were, but he is an intelligent man and a fine director. [7]

Bryan Singer: I had made so few movies, so I kept bringing up “The Usual Suspects.” And in the middle of the meeting, [Stan Lee] said, “Why do you keep bringing up that movie?” And I said, “I’m sorry, it’s just one of the few movies I’ve made.” He goes, “You made ‘The Usual Suspects’? Oh my god!” And I was like, “This icon has been treating me so nice, and he has no idea who the hell I am. Okay, I’d better take ‘X-Men’ seriously.” [6]

Stan Lee: He spent weeks, if not months, reading the books, talking to fans and the people who wrote them, trying to find out what it is about these characters that makes people interested. He learned his lesson, and I don’t think anyone could do the X-Men better than Bryan. [7]

Bryan Singer: I took [“X-Men”] on because the thematics of it were interesting to me. I saw Xavier and Magneto [played in the film by Ian McKellen] as Martin Luther King and Malcolm X characters. I’m gay or bisexual, whatever, so that probably [also] factored into [the decision to direct “X-Men”] because mutancy is discovered [during] puberty, when you’re different from your whole neighborhood and your family, and you feel very isolated. [8]

Chris Hewitt [journalist]: [The Variety announcement of the film read] “Singer Set to Direct Fox’s ‘Men.’” It’s an indication of how low the stock of comic book adaptations was at the time that Variety couldn’t even be bothered to get the title right. [9]

Bryan Singer: Chris McQuarrie and I went to an acting showcase. I stared at the floor for the whole time thinking, “How do I make an X-Men movie? How do I make an X-Men movie?” So we came up with some ideas to make it accessible to the non-fans as well as fans. [6]

The Script

A parade of screenwriters struggled to craft an “X-Men” screenplay (Singer and co-producer Tom DeSanto, an X-Men devotee who helped persuade Singer to direct, are credited with concocting the film’s story). After an attempt by Ed Solomon (“Men in Black”), Christopher McQuarrie was enlisted, following his work with Singer on “Public Access” and “The Usual Suspects.”

Christopher McQuarrie: Ed Solomon wrote a very fun popcorn movie—and that’s not what I do. I looked at it and said, “What if people were really mutants? What would the world be like if it was real?” [1]

Ed Solomon: I got fired initially because I chose to write a superhero movie where [the characters’] physical powers were external manifestations of their internal issues, and they were written as real human beings. I’m still to this day really proud that I was the first person to do that. [10]

Bryan Singer: Originally, one of the early writers had put Wolverine in the middle of [Magneto’s mutation] machine. “Why am I putting my main hero into a machine?” [I wondered]. “I need my main hero to rescue someone from a machine.” [So I] went into the office and said, “He’s out of the machine, Rogue is in the machine.” Casting Hugh Jackman was another [key decision]. And then the other was opening [the film] in the concentration camp. Those three things were pivotal. One set the tone, the other made the plot make sense, and then Wolverine was the audience’s eyes and ears into this new world. [9]

David Hayter [screenwriter, “X-Men”]: The Auschwitz scene was written by my friend Christopher McQuarrie, who is one of the greatest living screenwriters in the world. He did one pass on the script and came up with some amazing things. [11]

Christopher McQuarrie: I remembered reading that Magneto had these numbers on his arm, so I started writing [the opening scene set] in a concentration camp in Eastern Europe. Which is not where one traditionally starts comic book movies. [1]

Bryan Singer: Well, I’m Jewish, and as a Jewish person, you grow up with a very specific understanding of the Holocaust. An event like that is so overwhelming and incomprehensible…that I just became quite fascinated with it. [6]

David Hayter: [The opening] is the first thing I read of Chris’, in terms of “X-Men.” It was so stunning to me that we knew it had to be in the movie—and it’s basically unchanged from when Chris wrote it. All I did for the scene was translate the language into Polish. [11]

Bryan Singer: I don’t believe I’m equipped to make a “Schindler’s List” or a “Pianist” at this point in my life, but to be able to touch upon that subject matter in films like “Apt Pupil” or the beginning of “X-Men,” it’s interesting. It would be too hard for me emotionally to make a film that [was] day-in, day-out Holocaust. I don’t know how Steven [Spielberg] got through that experience. [6]

Unsatisfied with the existing drafts of the screenplay, Singer turned to an unlikely savior: his assistant, David Hayter, who had not been officially hired to write “X-Men.”

David Hayter: I was a depressed and broke film producer, and my friend Bryan Singer gave me a job answering phones on [“X-Men”]. He kept complaining about the script: “Nobody understands the X-Men, this script is going to ruin my life.” And I said, “Well, I know about the X-Men.” [11]

Tatiana Siegel [journalist]: Hayter had recently produced and starred in the Slamdance feature “Burn” and was an avid X-Men fan. Singer began to rely on Hayter for his comic book knowledge, and eventually, had him writing new scenes. [12]

David Hayter: I suggested a scene [between Wolverine and Cyclops] to Bryan. And Bryan said, “Good, go write that for me.” That kicked off 13 months of me working on the movie as a screenwriter. I had never been hired to write anything before. [11]

Bryan Singer: That’s where 50 percent of my work as a filmmaker goes, if not more: into the development of the script. [3]

David Hayter: [Bryan] started taking me to script meetings with Peter Rice and [Fox executive] Tom Rothman, and he would say, “Just sit there, take notes, don’t say anything, and don’t tell anyone you are writing the script.” [Producer] Ralph Winter knew and he asked me to highlight everything I’d done in the script at that point, and it was about 55 percent of the script. [12]

Tatiana Siegel: But other project insiders say Solomon and McQuarrie wrote the majority of what wound up onscreen, with contributions from Hayter. [12]

David Hayter: Ralph went to Peter Rice and said, “Look, here’s the deal. David, the phone guy, has been writing the script. You have to make a deal with him or we are in serious legal jeopardy.” Peter called me into his office and offered me $35,000 and said, “That’s all you’ll ever get. Be happy with that.” [12]

Bryan Singer: I’m pretty hard with writers; I’m not always pleasant, but I do seek to get the very, very best out of them, as they would expect me to give them my very best. Being fierce about every line of dialogue, about aspects of logic. A lot of writers think people won’t notice, or they’ll say, “That’s not a problem for me.” Well, it is a problem for me! And I think it’ll be a problem for the audience and their subconscious. [3]

David Hayter: While I am writing [“X-Men”], I never think I’m getting credit. In fact, Peter Rice [said], “You’ll never get credit. Don’t even think about getting credit.” So I figured I was just doing this for fun. Which is why I asked Bryan if I could have a small part [Hayter plays “museum cop”] in the movie, so I could remember that I was in it. [11]

Joss Whedon, who later wrote “Astonishing X-Men” comics and directed “The Avengers” (2012), also wrote a draft. Although he was long believed to have written only two lines in “X-Men,” Hayter says that much of Whedon’s work made it into the film.

David Hayter: Joss wrote a draft of the script while I was writing the script because the studio didn’t have any confidence in me—because I’d never written anything before. [11]

Joss Whedon: I am an “X-Men” guy. But I did read “The Avengers” pretty religiously before I read “X-Men.” And “The Avengers” took comics a step towards “X-Men” that I don’t think it gets credit for. [13]

Lauren Shuler Donner [producer, “X-Men”]: [Whedon’s draft] had humor in it. Bryan wanted this movie to be much more serious and more dramatic. [12]

David Hayter: Fortunately, Bryan was like, “The tone doesn’t really fit for me,” but there were a few things that we took from Joss’ draft that were so good, and one of them was [the first scene between Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart]. I think it’s beautifully done, I think the actors are incredible, and I love Ian’s line when he says, “They no longer matter!” It just echoes through the building. He’s got so much power. [11]

Whedon’s most controversial contribution was Storm (Halle Berry) gloating to Toad (Ray Park), “Do you know what happens to a toad when it’s struck by lightning? The same thing that happens to everything else.” To make matters worse, Singer developed a combustible relationship with Berry, which disintegrated further during the filming of “X2” (2003).

David Hayter: I thought it was a cool line. I could have taken it out, but I didn’t because I thought it worked. I think the reason people don’t like it is because it’s looped [rerecorded after the scene was filmed]. Because [Halle Berry] recorded it afterwards, it doesn’t feel like it matches her in the moment—and so it takes the power out of the line. [11]

Bryan Singer: I didn’t write it, but I do take full responsibility for it. It’s not one of my favorite lines in the movie. [14]

Halle Berry: Bryan’s not the easiest dude to work with. I would sometimes be very angry with him. I got into a few fights with him, said a few cuss words out of sheer frustration. [15]

Bryan Singer: I lose my temper sometimes when I wish I didn’t. I’d have a lot more joy in the process if I didn’t lose my temper. [3]

David Hayter: A lot of people knock Halle Berry’s performance, which is not fair. She did [a beautiful, subtle South African accent] through the entire film, and Bryan panicked at the last minute and said, “She shouldn’t have an accent.” He made her rerecord all of her dialogue with an American accent, except [for one] scene. And it feels like she’s not in the movie. Psychologically, the audience hears her and they don’t feel like she’s in the same room with everyone else, and it really was unfair to Halle. [11]

Halle Berry: When I work, I’m serious about that. And when that gets compromised, I get a little nutty. But at the same time, I have a lot of compassion for people who are struggling with whatever they’re struggling with, and Bryan struggles. [15]

The Cast

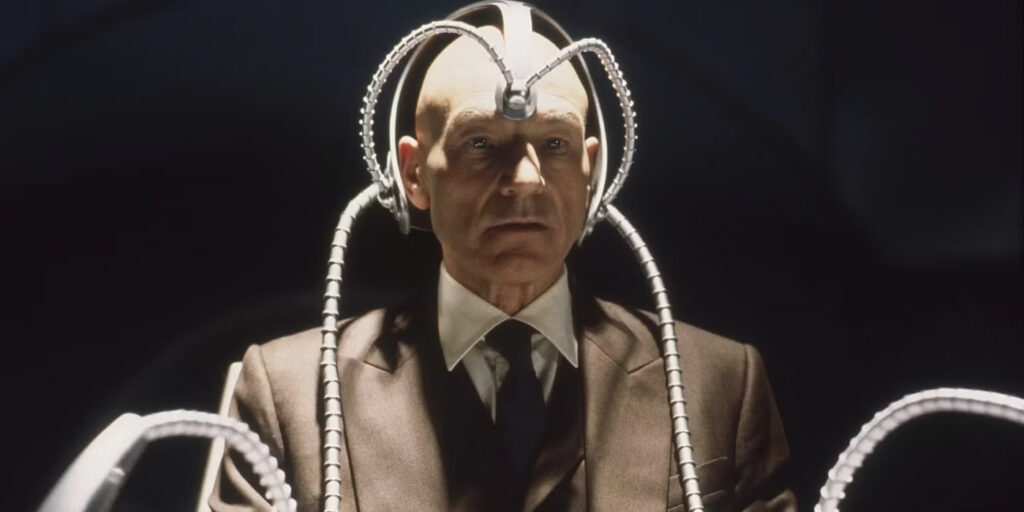

Arguably, the most crucial part in the film was Charles Xavier (a.k.a. Professor X), the bald, wheelchair-bound leader of the X-Men. Aristocratic and idealistic, Xavier seemed like a natural fit for Patrick Stewart, who had played Captain Jean-Luc Picard on “Star Trek: The Next Generation” (1987-94). Unfortunately, a meeting between Stewart and producer Lauren Shuler Donner proved disappointing.

Patrick Stewart: Seated behind her desk, [Lauren] greeted me by proffering a mocked-up photographic image of someone who looked like me sitting in a wheelchair. “What on earth is that, Lauren?” I said. “Ha!” she said triumphantly. “It’s you, six months from now. You were born to be Professor Charles Xavier.” [16]

Bryan Singer: I like Professor X. I’m a director, and I feel like I have to hold this ship [of wares] together and he’s got the same job. Keyser Soze [from “The Usual Suspects” is] a cool character too, obviously, but I don’t like him. He killed his family. [17]

David Hayter: [Terence Stamp] really wanted to be Professor Xavier—and at the time, Patrick Stewart was refusing to do the role. Terence told us, “You know why? It’s because of the chair. He doesn’t want to be stuck in the chair the whole time. But you know, I really do look exceptionally good bald.” [11]

Patrick Stewart: Needless to say, I soon thereafter found myself having lunch with Bryan Singer. A confident young man, he patiently heard my issues as I laid them out, never once interrupting me. But when he knew that I was done speaking, he presented his case. [16]

David Hayter: Patrick said, “I don’t want to do these genre things for the rest of my life.” And Bryan said, “Okay, but Patrick, remember: Harrison Ford was Han Solo until he was Indiana Jones.” That’s what convinced Patrick Stewart to sign on. [11]

Patrick Stewart: Our cast got along famously, though Bryan Singer was so fixed in his vision for the film that his demeanor sometimes bordered on authoritarian. Still, he kept his promise to keep our stories rooted in humanity rather than superhero hyperreality. [16]

Bryan Singer: You need to be able to answer [actors’] questions. [Patrick] said, “Bryan, why am I in this wheelchair?” And I said, “Well, I think years ago, your frenemy, Magneto, put you in that wheelchair.” He goes, “What does it say in the comic book?” “Well, in the comic book, it says that after traveling to Israel, Professor Xavier went to Tibet, where he encountered an alien agent named Lucifer, who had holed up in a castle. And so, Xavier rallied the Tibetans, fighters that they are, to assault this castle—and this angered Lucifer and he dropped a rock on the professor, and that’s why he’s in the wheelchair.” Patrick just looked at me and said, “I like your version better.” “Okay, we’ll go with that one for now.” [4]

While Xavier is committed to mutant-human coexistence, Magneto, who commands the Brotherhood of Mutants, is a cynic and an extremist. The greatest of all X-Men antagonists, he would be played by Ian McKellen, who had starred in Singer’s box office flop “Apt Pupil” (1998). At the time, he and Patrick Stewart were hardly friends.

Patrick Stewart: When I told [Ian that] I was going to sign the contract [to do “Star Trek: The Next Generation”], he almost bodily prevented me from doing so. “No!” he said. “No, you must not do that. You must not. You have too much important theater work to do. You can’t throw that away to do TV. You can’t. No!” [16]

David Hayter: Bryan saw [1998’s “Still Crazy”] and he said, “I think I found our Magneto.” And it was Bill Nighy. [Bryan] was like, “I’m going to discover this guy,” and he flew to London to meet with him, but then he came back and was like, “[He’s] not quite right.” [11]

Ian McKellen: Bryan Singer was casting this old Nazi [character] living in California [in “Apt Pupil”]. We met and he said, “Oh, you’re too young. What a pity.” We had a nice meal together and towards the dessert, he said, “Have you seen [‘Cold Comfort Farm’]? Who was the old guy who played the preacher?” I said, “That was me.” He said, “You play old?” I said, “Yes, I’m an actor.” So he gave me the part and then he put me in two “X-Men” [films]. [18]

David Hayter: Ian was concerned about playing a supervillain. But they had built him a bodysuit that he was going to wear—and when he wore it, he looked so buff. That was a big motivator towards embracing Magneto. [11]

Ian McKellen: I’ll tell you what, I’ve still got [the bodysuit] at home. [19]

Patrick Stewart: Ian and I had barely worked together—never in our days in the Royal Shakespeare Company and just once in London, in Tom Stoppard’s play “Every Good Boy Deserves Favour,” which had an extremely limited run. [16]

David Hayter: [McKellen and Stewart] were very wary of each other at the beginning. And then by the end, they were the best of friends. [11]

Bryan Singer: Whenever I see actors do what they do, they really intimidate me. And yet when I’m on set, because it’s my set and my movie, I have no problem somehow telling them what to do. In fact, Ian McKellen once [asked], “Bryan, could you possibly give me any other direction besides ‘less theatrical’?” [6]

David Hayter: Ian just was not sure what the role was on this day [of filming a scene in Magneto’s lair]. This was very early very on…and he kind of took it out on me. Which is fine. [11]

Patrick Stewart: In the years since, [Ian and I] have become dear pals and “X-Men” colleagues, and Ian has acknowledged that he was wrong [about “Star Trek”] and I was right. More than once, in fact—primarily because I like making him say those words. [16]

Perhaps the most vexing role to cast was Logan/Wolverine, the amnesiac Canadian bruiser who becomes one of the most ferociously loyal members of the X-Men. Numerous actors were fielded before Dougray Scott, the Scottish star of “Ever After” (1998), was selected.

David Hayter: All of the artwork, when I came [onto] the movie, featured Mel Gibson as Wolverine. [11]

Bryan Singer: Before I ever met Hugh Jackman, I asked Russell Crowe to play Wolverine. He said, “I’ll do it! I’ll do it bald!” [20]

Russell Crowe: If you remember, Maximus [in “Gladiator”] has a wolf at the center of his cuirass, and he has a wolf as his companion at the beginning of the film, which I thought was going to be a bigger deal. So I said no [to “X-Men”], because I didn’t want to be “Wolfy the general” and then “Wolfy the other bloke,” like now I’m Mr. Wolfman. [21]

David Hayter: We met with [Viggo Mortensen]. He walked out and I was like, “That guy’s a movie star.” And then I came out of my office and at the end of the hall, there was Viggo. He had been wearing cowboy boots, [but] now he’s in his bare feet. He goes, “I realize that Wolverine isn’t that tall. I’m really not that tall and I wanted Bryan to see that.” [11]

Viggo Mortensen: [I took my son] Henry to the meeting I had with [Bryan Singer] as my sort of good luck charm and guide. In the back of my mind, I was thinking he could learn something, too, because I did let Henry read the script and he goes, “This is wrong. That’s not how it is.” [22]

David Hayter: He had just come from camping with his son. I guess his son had told him why “X-Men” was cool and why he should do this role. [11]

Viggo Mortensen: All of a sudden, [Singer] is falling all over himself and then the rest of the meeting was him explaining in detail to Henry why he was taking certain liberties [with the source material]. We walked out of there, and Henry asks if [Singer] will change the things he told him about, and I say, “I don’t think so. I’m not going to do it anyway, because I’m not sure I want to be doing this for years.” And then, a couple of years later, I’m doing three “Lord of the Rings” [movies] so who knows. [22]

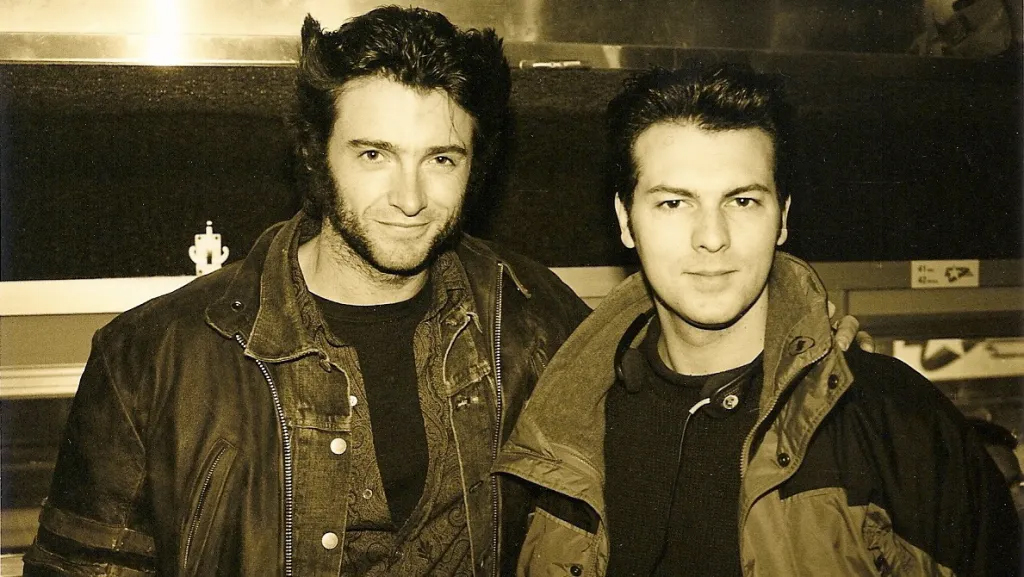

At the time, Scott was starring opposite Tom Cruise in John Woo’s “Mission: Impossible 2” (2000). When the sequel fell behind schedule, a new Logan was needed—presenting an opportunity for Australian actor Hugh Jackman, who had previously been turned down for the part.

David Hayter: I was there for pretty much all of the casting, and the first time Hugh Jackman read, he didn’t get cast. He was great, but he was the nicest guy in the world and he was very tall and super handsome, so we didn’t think he was Wolverine. [23]

Bryan Singer: I really had no work experience with [Dougray Scott]. I just knew that I had cast him, and when he suddenly became unavailable, we were in the middle of shooting. [24]

Dougray Scott: I never wanted [to play Logan] anyway. I was really persuaded by Fox to do it, and then when I decided to do it, I was training very hard, but it was out of my control; “M:I-2” was going on too long and there was not much I could do about it…but good luck to Hugh, who plays it very well. [25]

David Hayter: Lauren Shuler Donner said, “Let’s bring back Hugh Jackman.” So she had him flown out and they did coaching sessions with him to really get him to that sort of Clint Eastwood, hard-ass edge. [23]

Patrick Stewart: [While] Ian, Halle, James [Marsden], and I were sitting around drinking coffee and waiting for a lighting setup to be completed, a production assistant escorted [Hugh in] and introduced him to us. He was a handsome, dark-haired fellow with a relaxed, amiable manner, and he explained that he had come to meet Bryan and be put on camera for a screen test. [16]

David Hayter: We are literally auditioning Hugh Jackman in the back room while [the scene featuring Jean Grey’s speech about mutation] is being filmed. [11]

Patrick Stewart: We were all rooting for [Hugh]—he had that intangible star quality. But he also had a thick Australian accent. Would that disqualify him? We wondered if he would be able to cover it up, maybe working with a dialect coach. [16]

Hugh Jackman: Anyone who knows me knows that I couldn’t be further from Wolverine. Even my kid, I’ve heard friends of [his] say, “Oh, your dad, Wolverine,” and he’ll go, “He’s nothing like Wolverine. He is not cool, he is not tough, nothing like that, okay?” [He] just shuts it down immediately, and he’s absolutely right. [26]

Patrick Stewart: About half an hour passed before Hugh returned [after his final audition]. This time, his air of easy confidence was gone. “How did it go?” someone tentatively asked. Hugh shook his head mournfully. “Well, you guys are never going to see me again,” he said. We let out a collective groan and rose to console him. But right at that moment, Hugh was summoned by one of the producers into another meeting. “Poor guy,” I said. “I bet they’re going to offer him a bit part as consolation.” [16]

Bryan Singer: I looked quite young at this time and I was off to the side wearing my headphones, just listening to [Hugh’s audition]. So a janitor came up to me—didn’t know who I was—and was like, “Hey! Dude! Is that the guy they got to play Wolverine?” And I was like, “This is the moment.” So I went, “Yeah.” I’m looking at the guy, and he just goes, “Cool.” [24]

Patrick Stewart: We sat in the gloom for a few minutes, pondering how brutal our business is. Then the same poor guy returned to our cluster of chairs with a dazed look on his face. The producer escorting him said to us, “Ladies and gentleman, meet Wolverine!” [16]

David Hayter: I think one thing Hugh captured with Wolverine is his heart. Hugh is such a lovely, caring guy, and that really came through in the character. All that was left was to find the viciousness. [23]

Hugh Jackman: I see an epic nature to this character and what he represents in terms of human nature. It seems to me that finding the balance of being a natural human being is ever tougher in our modern world. So you hear those ridiculous stories about men going into the forest in loincloths and chanting. They’re absolutely bored with their lives. You just have to go on the subway and there seem to be a lot of people walking around half-dead. [30]

Patrick Stewart: [Hugh] told us later that he had been about to head straight for the airport when he emerged from his audition with that disconsolate look on his face. Instead, he was whisked off to the wardrobe department for an urgent costume fitting. Our business is not only brutal, but at times quite insane. [16]

The Endgame

With a release date that was bumped up from December to July 2000 and a $75 million budget (a modest sum for a superhero film), “X-Men” turned into a torturous production. Amid the tumult, Singer missed his closest collaborator: composer and editor John Ottman, who was busy directing the doomed horror sequel “Urban Legends: Final Cut” (2000).

John Ottman: Bryan’s used to me telling him, “This is what we need to do.” I guide the process [of composing the film’s score] with him. [“X-Men” composer] Michael Kamen was more of a guy saying, “What do you want me to do?” Bryan was like, “I don’t know.” [28]

Michael Kamen: [“X-Men”] was very, very tough. Fox was having a little difficulty with the film and everybody was a little nervous and nobody knew what it would be. [29]

John Ottman: Because Bryan and I idolize films of the seventies, he told Michael Kamen, “I want to do a seventies score.” But that’s not what he meant—and I’m paraphrasing Bryan. Our sensibilities are born from the seventies films; it doesn’t mean we’re making a seventies score exactly. [28]

Michael Kamen: I worked on it for probably three or four months longer than most films take. I parted on good terms with Bryan, but we haven’t been in touch much since. [29]

John Ottman: I had heard [about] the horror stories and the complete cataclysm behind the scenes that was going on—and when I went to see the film, it seemed fine to me. They did a lot of surgery, but they did it so well I was unaware of what they actually did. [28]

Michael Kamen: I try to remember that I am a real person. It’s not hard to do; I behave very much like a real person. Music isn’t pretend, though some guys get away with it. [30]

With Ottman also unavailable to edit “X-Men,” Steven Rosenblum, Kevin Stitt, and John Wright (who died in 2023) were recruited. According to recollections, tempers erupted as Singer bemoaned Ottman’s absence and the editors struggled to condense hours of chatty footage into a compelling film.

David Hayter: There were 47 extra minutes [that got cut out]. It was people talking about Wolverine or how they feel about this or how they feel about that. And it was so long [and talky] that we called the first cut “Woody Allen’s X-Men.” [11]

Bryan Singer: [One of the film’s editors] didn’t have a lot of faith in me or thought I was too young. It got kind of ugly and made the experience very upsetting and frustrating to me. [31]

John Ottman: I felt sorry for the main editor [of “X-Men”] because Bryan would always remind him, “Well, John would do this, John would do that”—to the point where the guy was like, “If you mention John’s name one more time, I’m going to kill you.” [28]

Bryan Singer: I got into such a fight with [an “X-Men” editor] in his office. I [watched] a scene and I didn’t like the way he cut it. I was so young and so stupid…that I took a bottle and I smashed it on the wall. So [the editor] came in, saw that I smashed the bottle, and locked me out of the editing room for three days. My own editing room on my own movie. I had to get the president of the studio involved…it was a whole awful thing. [31]

Lauren Shuler Donner: [Bryan] was very nervous and he would act out when he was insecure, as many people do. But his way of acting out would be to yell and scream at everybody on the set. Or walk off the set or shut down production. [12]

David Hayter: We were one day [behind] schedule [at one point] and the studio freaked out so badly that the studio president came up and the vice president came up—and they were telling Bryan, “You need to catch up.” So he shot one take [of the scene we were filming], looked at it, and said, “Okay, good. Cut. Moving on. There. We’re caught up. Go home.” And he put on his cap and he walked off set. [11]

John Ottman: Unfortunately, my not doing “X-Men” increased Bryan’s conviction [that I had to both score and edit his movies] because he said he lost 10 years of his lifespan without me on that film. [28]

David Hayter: Bryan, the editors, Tom Rothman, [and executive producer] Avi Arad went through piece by piece and cut every single thing they could. That’s when [the film] worked. [11]

Bryan Singer: Since Peter [Rice] was my only real friend at the studio…I took a walk through the parking lot outside Building 88, which is the production building at Fox, and it was just the two of us. I looked [to] Peter, almost as a therapist, because there was no answer he could give me. I said, “If this film fails financially and critically, I will never be able to make one of these again.” He said, “Well, I hope it doesn’t.” [4]

The Aftermath

On July 14, 2000, “X-Men” was released. It earned over $296 million worldwide and the enthusiasm of critics like The New Yorker’s David Denby, who wrote, “Bryan Singer, the greatly talented director of the Hollywood cult favorite ‘The Usual Suspects,’ is back on top after his misadventures with the dreadful ‘Apt Pupil’—and this time, I suspect, for good.”

Bryan Singer: The premiere of the movie was held on Ellis Island [where part of the film’s climax is set] with boats to take the audience out; the great hall was converted into a giant movie theater; and we had an “X-Men” blimp and we had fireworks over the Statue of Liberty. It was quite amazing. [14]

David Hayter: The first time I saw the movie was [at] a press screening. The first guy in line—[he] must have been there two hours—[was] wearing a Wolverine cap. He pointed at me and he’s like, “Why does he get to go in first?” My friend, who was being all arrogant, goes, “Because he wrote the movie.” And the guy says, “Well, I created Wolverine.” So the first time I watched [“X-Men,” Wolverine creator Len Wein, who died in 2017] was sitting behind me in the theater—and then as soon as we sat down, I was like, “He’s going to be judging me.” In the end, he was really happy, and that meant a lot to me. [11]

Hugh Jackman: Funny enough, I remember catching a plane while we were promoting “The Prestige” with [“Dark Knight” trilogy director] Chris Nolan, [who] said to me that he’d always had Batman in his mind. He said, “When I went into the cinema and saw ‘X-Men,’ I said, ‘Damn, that’s my idea.’” The idea [was] that you could really dive into the emotional life, into the vulnerability of these characters and that…is what’s going to hook people and make them care. That’s what Bryan did, [and] he had a lot of courage to do that. [32]

Bryan Singer: When [“X-Men”] opened, Rebecca Romijn [who played Mystique] and [her then-husband] John Stamos and I went over to pick up Howard Stern and took him over to the Ziegfeld Theatre to watch the movie. Halfway through the movie, it was the scene where Magneto is lifting up the police cars [and Stern] leaned over, looking down at me and said, “This is fucking great!” I thought, “That’s five or 10 million listeners right there!” He actually asked me to come on [his] show, but I was terrified he might unearth my personal life, so I didn’t go. [9]

Hugh Jackman: “X-Men” was the turning point, I believe, in terms of comic book movies and I think there’s a lot to be proud of. And there’s certainly questions to be asked and I think they should be asked. [33]

In the aftermath of the allegations against Singer, “X-Men” cast and crew members have publicly reflected on their time working with him. Their ruminations have been, to say the least, conflicted.

Hugh Jackman: I think there are some ways of being on set that would not happen now. And I think that things have changed for the better. [33]

Lauren Shuler Donner: It’s a weird business, the film business. We honor creativity and talent and we forgive the brilliant ones. Unconsciously, we probably do enable them by turning a blind eye to whatever they’re doing and taking their product and putting it out to the world. [12]

Rebecca Romijn: [Bryan Singer] sometimes didn’t come in prepared. But he would show up and, without any preparation whatsoever, direct the most awesome scene that he was able to put together because he’s such a good filmmaker. [34]

Lauren Shuler Donner: You have to understand, [Bryan] was brilliant, and that was why we all tolerated him and cajoled him. And if he wasn’t so fucked up, he would be a really great director. [12]

David Hayter: To actually watch a film that I’ve worked on, I don’t find [that] to be particularly fun. I can’t watch the “X-Men” movies without being like…“Remember that horrible day?” [35]

Lauren Shuler Donner: Listen, I love Bryan, but Bryan has a lot of demons. [He] needs to take care of his personal problems. That’s all I can say. [36]

The Legacy

David Hayter received sole “screenplay by” credit for “X-Men” and remained in the realm of superhero cinema, co-writing Zack Snyder’s “Watchmen” (2009). He has also voiced two characters in the “Metal Gear” video game series (Solid Snake and Naked Snake) and hosted the 2023 podcast “Unauthorized,” a chronicle of his experience writing “X-Men.”

Since first donning Logan’s claws, Hugh Jackman has starred as P.T. Barnum in “The Greatest Showman” (2017) and earned an Oscar nomination for playing Jean Valjean in “Les Misérables” (2012). He has appeared in 10 “X-Men” films, despite vowing to retire from the franchise after 2017’s “Logan” (2024’s “Deadpool & Wolverine” featured his surprise return to the role).

Following a falling out (one of several), Christopher McQuarrie re-teamed with Bryan Singer for “Valkyrie” (2008), starring Tom Cruise. Since then, McQuarrie has become a trusted lieutenant in Cruise’s inner circle, directing four “Mission: Impossible” films and co-writing and producing “Top Gun: Maverick” (2022). The director and star will reunite for the upcoming “Broadsword,” which McQuarrie has described as a “gnarly movie.”

Peter Rice eventually became president of Fox Searchlight, overseeing indie hits like “Napoleon Dynamite” (2004). Though Fox was sold to Disney in 2017, Rice migrated to the Mouse House—only to be fired in 2022 by then-CEO Bob Chapek. Subsequently, Rice signed a nonexclusive producing deal with the hip arthouse distributor A24 and produced Sony’s “28 Years Later” (2025), which was a modest hit.

Bryan Singer directed three more “X-Men” films: “X2,” “X-Men: Days of Future Past” (2014), and “X-Men: Apocalypse” (2016). Prior to the publication of the Atlantic exposé that disrupted his career, he was fired shortly before he was slated to finish filming the Freddie Mercury biopic “Bohemian Rhapsody,” which would go on to net four Oscars and over $910 million worldwide. In the years since, Singer has continued to work, directing an upcoming feature (starring Jon Voight) and developing a documentary about “his struggles.”

The quotes used in this article have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Sources Cited

[1] Goldsmith, J. (2019, March 23). “‘Valkyrie’ Q&A – Christopher McQuarrie.” The Q& A with Jeff Goldsmith. http://www.theqandapodcast.com/2019/03/valkyrie-q-christopher-mcquarrie.html.

[2] Mitchell, E. (2006, June 28). “Bryan Singer.” The Treatment. https://www.kcrw.com/culture/shows/the-treatment/bryan-singer.

[3] Francis, P. (2023, January 31). “Bryan Singer: Confidence Man.” MovieMaker. https://www.moviemaker.com/bryan-singer-confidence-man-3221.

[4] (2016, September). “Gamechangers: Peter Rice and Bryan Singer.” YouTube; Edinburgh TV Festival. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=–HAWuMp_TQ&t=235s.

[5] (2023, July 4). “Christopher McQuarrie: Story Structure, Screenwriting, Directing & ‘Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning.'” YouTube; The Filmmaker’s Podcast. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rPn0PYCfudI&t=2208s.

[6] (2013, August 8). “Rated-X: A Night with Bryan Singer Part 2.” YouTube; cruise_net. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zwhFiKNqDtM&t=3s.

[7] Dilullo, T. (2004, August). “Stan the Fan.” Sci-Fi: The Official Magazine of the Sci-Fi Channel.

[8] Chitwood, A. (2016, April 20). “Bryan Singer on ‘X-Men: Apocalypse,’ Superhero Movies.” Collider.com. https://collider.com/bryan-singer-x-men-apocalypse-interview.

[9] Hewitt, C. (2014, March). “Super-Man Returns.” Empire.

[10] Evry, M. (2020, August 27). “Exclusive: Screenwriter Ed Solomon Talks His Involvement in ‘X-Men.'” Comingsoon.net. https://www.comingsoon.net/movies/features/1146797-exclusive-screenwriter-ed-solomon-talks-his-involvement-in-x-men.

[11] Hayter, D. (2023, March 23). UNAUTHORIZED: with David Hayter. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/unauthorized-with-david-hayter/id1678419536.

[12] Siegel, T. (2020, July 31). “Bryan Singer’s Traumatic ‘X-Men’ Set: The Movie ‘Created a Monster.'” Hollywood Reporter. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/bryan-singers-traumatic-x-men-set-movie-created-a-monster-1305081.

[13] Rogers, A. (2012, May 3). “Joss Whedon on Comic Books, Abusing Language and the Joys of Genre.” Wired. https://web.archive.org/web/20170822034235/https:/www.wired.com/2012/05/joss-whedon/all/1#start-of-content.

[14] Singer, B., & Peck, B. (2009, April 21). “X-Men” audio commentary. Twentieth Century Fox.

[15] Setoodeh, R. (2020, September 9). “Halle Berry Recalls Fights With Bryan Singer on ‘X-Men’ Movies.” Https://Variety.com/2020/Film/News/Halle-Berry-x-Men-Fights-Bryan-Singer-1234762756/; Variety.

[16] Stewart, P. (2023, October 3). “Making It So: A Memoir.” Gallery Books.

[17] (2013, August 8). “Rated-X: A Night with Bryan Singer Part 6.” YouTube; cruise_net. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6MqOxo-CNzc&t=8s.

[18] (2018, December 1). “Ian McKellen on Becoming X-Men’s Magneto | BAFTA Insights.” YouTube; BAFTA Guru. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-PPm0Hvj3Qg.

[19] (2018, November 7). “Sir Ian McKellen Still Wears Magneto’s Bodysuit!” YouTube; The Graham Norton Show. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0y9rl41-H-s.

[20] (2013, August 8). “Rated-X: A Night with Bryan Singer Part 3.” YouTube; cruise_net. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gdefnujvBL0&t=4s.

[21] Pearson, B. (2017, May 22). “Here’s Why Russell Crowe Turned Down Playing Wolverine In Bryan Singer’s ‘X-Men.'” /Film. https://www.slashfilm.com/551094/why-there-was-no-russell-crowe-wolverine.

[22] Romano, N. (2021, February 9). “Viggo Mortensen recalls turning down the role of Wolverine in the X-Men movies.” Entertainment Weekly. https://ew.com/movies/viggo-mortensen-wolverine-x-men.

[23] Vanhooker, B. (2022, March 3). “The oral history of Wolverine, the unlikely superhero who saved the X-Men.” Inverse. https://www.inverse.com/entertainment/wolverine-oral-history-x-men.

[24] (2013, August 8). “Rated-X: A Night with Bryan Singer Part 5.” YouTube; cruise_net. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yoUpVk1x-iI&t=204s.

[25] Thompson, J. (2006). “Where Are They Now? Dougray Scott.” Wizard: The Magazine of Comics.

[26] Horowitz, J. (2014, December 15). “Hugh Jackman.” Happy Sad Confused. https://podcasts.apple.com/my/podcast/hugh-jackman/id827905050?i=1000327425365.

[27] Schneller, J. (2006, September). “Brave Hugh World.” Premiere.

[28] Bijan, R. (2015, April 17). “Backseat Filmmaker Ep 5 – The Films and Music of JOHN OTTMAN, Pt 1/2: UNCANNY ORIGINS.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D6Ua1BIlFLU.

[29] Stax. (2001, October 26). “Kamen Settles ‘X-Men 2’ Score.” IGN. https://www.ign.com/articles/2001/10/26/kamen-settles-x-men-2-score.

[30] Mangodt, D. (1996). “An Interview with Michael Kamen by Daniel Mangodt.” Soundtrack Magazine. https://cnmsarchive.wordpress.com/2013/07/23/michael-kamen.

[31] (2013, August 8). “Rated-X: A Night with Bryan Singer Part 4.” YouTube; cruise_net. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zIyYpUh6Uns&t=5s.

[32] Stephens, N. (2021, August 5). “Hugh Jackson says that ‘X-Men: Days of Future Past’ will blow everyone away.” JoBlo. https://www.joblo.com/hugh-jackson-says-that-x-men-days-of-future-past-will-blow-everyone-away.

[33] Godfrey, C. (2023, January 5). “‘I’m not always nice’: Hugh Jackman on anger, vulnerability and the loss of his father.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2023/jan/05/hugh-jackman-wolverine-father-the-son-x-men.

[34] White, A. (2023, July 5). “Rebecca Romijn Addresses Why She Didn’t Speak Out Amid #MeToo Allegations Against Bryan Singer, Brett Ratner.” Hollywood Reporter. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/rebecca-romijn-bryan-singer-brett-ratner-allegations-1235529625.

[35] Horner, A. (2020, July 14). “Episode 3: ‘Watchmen’ with David Hayter.” Script Apart. https://www.scriptapart.com/episodes/episode-3-watchmen-david-hayter.

[36] Topel, F. (2018, January 5). “‘X-MEN’ PRODUCER WELCOMES AVENGERS–X-MEN CROSSOVER, WEIGHS IN ON HOLLYWOOD HARASSMENT.” Rotten Tomatoes. https://editorial.rottentomatoes.com/article/x-men-producer-lauren-shuler-donner-on-avengers-x-men-and-hollywood-harassment.