The question was about the future of cinema, but Robert De Niro wanted to talk about the future of America.

“I’m worried,” De Niro said during a Q and A in September. “To me, it’s not over till it’s over. And we have to go at this wholeheartedly…[to] beat Trump. It’s that simple. Everybody has to get out there and vote. And we have to make it very clear what America is.”

Two months later, it became clear what America is: a nation whose citizens are willing to vote for a fascist and a felon who ignited an insurrection with a temper tantrum. As a movie politician once said, “This is how liberty dies—with thunderous applause.”

Go ahead, tell me, “It was the economy and the border, stupid.” My response is the same as it ever was: a vote for Trump may well be a vote to put children in cages. Try justifying that.

When the rule of law and the sanctity of life are threatened, making a list of movies can seem laughably inconsequential (well, more laughably inconsequential than usual). Nevertheless, at the risk of misappropriating Senator Elizabeth Warren’s battle cry, I’m persisting.

Why? Not only because I want to (duh), but because it’s worth celebrating the ways in which movies can be potent and unpredictable weapons in the hands of the resistance.

From the arthouses to the multiplexes, films from the first Trump term sharpened our anti-authoritarian instincts, preparing us to face the 45th president’s lethal incompetence during the pandemic and the attempted coup on January 6, 2021.

No, movies couldn’t stop Trump from condemning countless COVID-19 patients to death by sadistic negligence. But cinematic rallying cries like “Black Panther” (2018), “A Hidden Life” (2019), “Knives Out” (2019), and “mother!” (2017) kept us angry and alert, reminding us that normal doesn’t equal right.

In 2024, cinema staged a preemptive strike against resurgent Trumpism. “Dune: Part Two” was a blow to doe-eyed totalitarians everywhere; “Evil Does Not Exist” bent greedy humans to mother nature’s mystical will; and “Megalopolis” put an arrow in the buttocks of fascism itself.

Can movies rescue us from the next four years? I wish. Cinema can move us, distract us, or enlighten us, but it can’t save us from the worst angels or our nature. Only we can do that.

Then again, emotion, distraction, and enlightenment can mean the difference between victory and defeat. This is how liberty survives—through thunderous art.

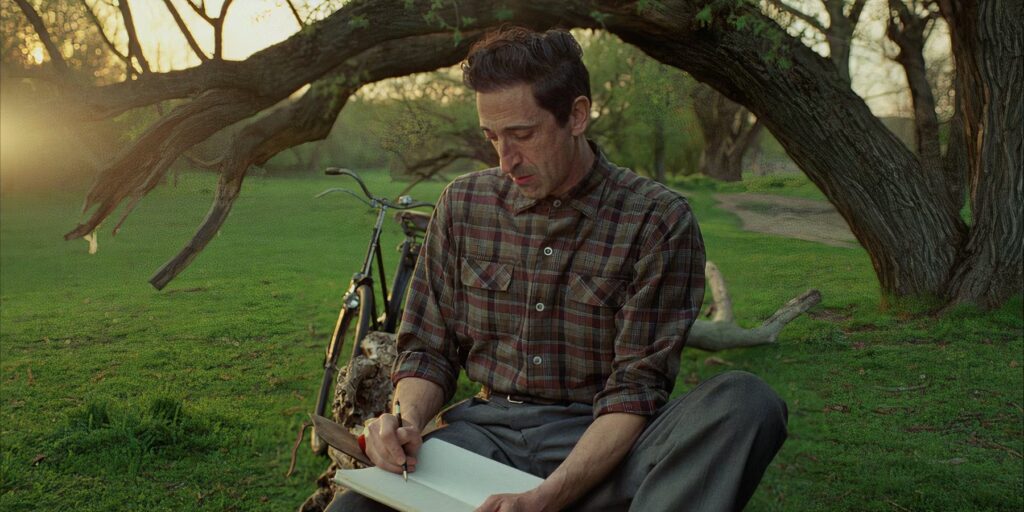

1. “The Brutalist”

The themes of Brady Corbet’s “The Brutalist”—capitalistic conquest, agonizing assimilation, self-immolating visionaries and their envious rivals—echo mighty American epics like “Citizen Kane” (1941), “The Godfather” (1972), and “Oppenheimer” (2023).

I know; it all sounds like homework. But “The Brutalist,” which Corbet wrote with Mona Fastvold, is a movie worth cutting class for: brashly political, bluntly sensual, eerily hilarious, and earthshakingly beautiful to behold.

Beauty is the life’s work of László Tóth (Adrien Brody), a Hungarian-Jewish architect trapped in an increasingly toxic bromance with Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce), a suave industrialist who schools László in the nightmarish realities of the American Dream.

“They don’t want us here!” László shouts. Yet you want to be wherever László is: on a bus rocketing down a highway, in a train station where he reunites with his wife, Erzsébet (Felicity Jones), or in a quarry that haunts the film like a spectral dream.

As a full-course cinematic meal, “The Brutalist” is so scrumptious that I feel perversely compelled to criticize its few fumbles: the prankish finale, the sideways-scrolling credits, the ponderous chapter titles (e.g. “The Enigma of Arrival,” presumably an allusion to Nobel laureate V.S. Naipaul’s autobiography).

Those arty affectations are a sure sign that Corbet and Fastvold tried too hard to make a masterpiece. Nevertheless, a masterpiece is what they have made.

2. “Babygirl”

A woman walks into a dance club, framed by a halo of green light. In silhouette, she looks powerful, towering—but as she wades into a rave, an ocean of acrobatic bodies overwhelms her.

Dancers fill her field of vision; she makes out with someone she’s never met; she buckles under the beat of “CRUSH,” a throbbing techno anthem by Natte Visstick, RHYME, and Yellow Claw (“I try to be a good girl/But I wanna feel alive”).

Then, she spots a young man, a familiar, slender form amid the masses. Once he takes her hand, the crowd that seemed so terrifying in its vastness begins to feed into the couple—into their energy, their chemistry, their movement.

Moments later, the woman and the man vanish into a maze of pinkish hallways to make love. You don’t know precisely where they’re headed, but you know they’ll be all right. As with all labyrinths, the only way out is through.

3. “Megalopolis”

“I’m not concerned with my place in history,” Cesar Catilina (Adam Driver) declares in Francis Ford Coppola’s “Megalopolis.” “I’m concerned with time.”

Those words remind you that Coppola, who is 85, is running out of time. I’m grateful that he’s still with us—and that he devoted a few of his remaining years to “Megalopolis,” a ferociously idealistic fantasy about art triumphing over autocracy.

“There’s nothing to be afraid of if you love, or have loved,” Cesar tells a reporter (played by a live actor at some screenings). “It’s an unstoppable force.”

In “Megalopolis,” Coppola harnesses that force using the power of camp, romance, sci-fi, and slapstick. Dismissing the movie as silly and melodramatic is easy; acting upon what it says about the past, present, and future is hard.

“I pledge allegiance to our human family, and to all the species that we protect,” a chorus recites as the film concludes. “One Earth, indivisible, with long life, education, and justice for all.” And mega-movies, too.

4. “Dune: Part Two”

Last November, Denis Villeneuve was asked why he makes movies about “a cycle of violence.” “Because we’re stuck with it,” Villeneuve said with a rueful chuckle. “Because I want to find a way out.”

In “Dune: Part Two,” Villeneuve doesn’t find a way out, but he vividly dramatizes that cycle, blurring the line between victor and victim by bookending the film with the same image: a heap of corpses set aflame.

“Our enemies are all around us, and in so many futures they prevail,” murmurs Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet). “But I do see a way. There is a narrow way through.”

Turns out the “narrow way” involves mass murders and the manipulation of Indigenous peoples. After the dawdling of “Dune: Part One,” “Part Two” embraces the grim jest of Frank Herbert’s novel: a callow protagonist is always one hero’s journey away from becoming a callow tyrant.

Subversive stuff for a sci-fi blockbuster, even if subversive isn’t shocking coming from the French-Canadian Villeneuve, who cut his teeth on comedies about horny Canucks (1998’s “August 32nd on Earth”) and talking fish (2000’s “Maelström”).

From there, Villeneuve found his way into those cinematic cycles of violence. Now, he needs to find his elusive exit.

5. “Day of the Fight”

The last day in the life of “Irish” Mike Flanagan (Michael Pitt) is eventful. He pawns his mother’s ring. He lunches with his ex (Nicolette Robinson). He visits his abusive father (Joe Pesci). He trains for a fatal boxing match at Madison Square Garden.

Having been diagnosed with a brain aneurysm, Mike knows that his next fight will be his last—which doesn’t bother him because he doesn’t believe he deserves to live. Whether or not he’s right is a judgment that director Jack Huston (the grandson of John Huston) leaves to you.

Filmed in sharp-yet-soft black-and-white by Peter Simonite, “Day of the Fight” is a tough and tender elegy. Mortality liberates Mike, freeing him from his past sins to savor a day with strangers and friends in the city he loves—including Patrick (John Magaro), a priest and longtime pal.

“People think that penitence is some kind of punishment—that they have to punish themselves to somehow be redeemed,” Patrick tells Mike. “But that’s not what it is. It’s the journey that we take to understand what we did wrong. It’s the discovery and acceptance that redeems us.”

Now in his 40s, the once-boyish Pitt handles discovery and acceptance like a pair of well-loved boxing gloves. Mike will never grow old, but Pitt has aged beautifully, shedding his buoyancy in “The Dreamers” (2003) to play a man who is finishing up and just getting started, all in one tragic, exquisite day.

6. “My Old Ass”

Most coming-of-age movies are like LEGO sets, with clichés clicking together like plastic bricks: the twisted romance, the falling-out with a best friend, the climactic heart-to-heart with a parent or sibling.

None of those tropes are built into Megan Park’s “My Old Ass,” which is more like an Erector set: the gears of its plot fit perfectly, yet you’re amazed that it stands upright. I’m no expert, but I suspect movies about mushroom-imbibing teens meeting their future selves are rarely this good.

“Dude, I’m you,” Future Elliott (Aubrey Plaza) tells Present Elliott (Maisy Stella), before giving her some ostensibly irrefutable advice: stay away (like, away away) from everyone named Chad.

“My Old Ass” is the story of how (and why) Elliott breaks that rule, upending every tenet of teen cinema along the way. Park’s psychedelic shenanigans defy the genre’s normally dreary realism, yet even that defiance is a narrative feint, rendering us defenseless against an overpowering ending.

In the spirit of self-control, I’ll leave it at that. If you’ve seen “My Old Ass,” you know that it’s a movie you don’t want to spoil and want to spoil for everyone. Like growing up, it’s not just emotional; it is an emotion. Keeping it bottled up inside is impossible.

7. “Evil Does Not Exist”

Directed by Ryusuke Hamaguchi (“Drive My Car”), “Evil Does Not Exist” could have been a righteous saga of noble environmentalists defending their isolated home. And it is…until a brilliantly bizarro climax that depicts nature at its most glorious and its most ruthless.

Ryuji Kosaka and Ayaka Shibutani are movingly earnest as misguided urbanites championing a glamping site in a rural community, but the film’s center of gravity is Takumi (Hitoshi Omika), the “odd job guy” who teaches the interlopers a brutal truth: Earth is not ours to exploit, or even to protect.

That is the meaning of the movie’s seemingly endless opening montage of skeletal, godlike trees. In “Drive My Car,” the world was a backdrop for human drama; in “Evil Does Not Exist,” humans become the backdrop, waiting to be absorbed by wondrous, wrathful forces that they can never fully know.

“The locals are not as stupid as you think,” one character warns. Neither is Mother Nature.

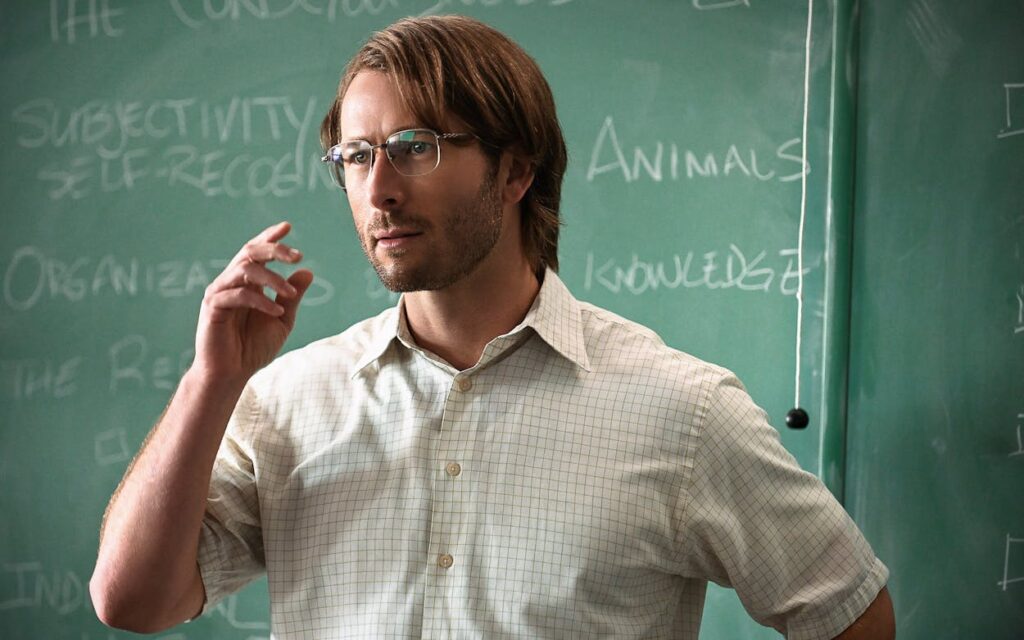

8. “Hit Man”

The best movie stars play themselves—or an idea of who we think they are. Thus, when you’re in the market for a lovably obnoxious overachiever, you cast the man who made a home-cooked meal out of the line “We’re goin’ into combat, son! On a level no living pilot’s ever seen!”

On and off the screen, the 36-year-old Texan Glen Powell seems desperate to be a movie star (he allegedly told Tom Cruise, his “Top Gun: Maverick” co-star, “I want your career”). For Powell, declining to cloak his ambitions in false humility isn’t a PR fail—it’s a signature move.

That move is the only move in “Hit Man,” which transforms the true story of Gary Johnson, a college professor who moonlighted as a fake hitman, into a playfully Powell-esque charade (the actor co-wrote the film’s screenplay with director Richard Linklater).

Eager to prove himself to the New Orleans Police Department, Powell-as-Gary conceals his professorial bona fides behind an outrageous panoply of wigs and accents, throwing himself into sting operations with the gusto of an actor trying to win an Oscar.

Of course, Powell probably is trying to win an Oscar, but that’s not a minus. In “Hit Man,” he seems to revel in his cosmic celebrity dreams and cheerfully mock them, exuding seductively smug charm that is thoroughly authentic in its artificiality.

Can Powell’s self-generated hype withstand the exposure of coming collaborations with J.J. Abrams and Edgar Wright? I wouldn’t bet against him. We’re goin’ into movies, son. On a level no living moviegoer has ever seen.

9. “Joker: Folie à Deux”

How about a joke? A filmmaker helms a comic-book fable about the horror of living in a society with little healthcare and less gun control—and is accused of making a movie that is sympathetic to the online misogynists known as incels.

So, the filmmaker directs a sequel that vociferously decries incels…and it becomes one of the worst-reviewed follow-ups since “Speed 2: Cruise Control” (1997). Who’s laughing now?

Not Warner Bros., which may have lost more than $150 million when “Joker: Folie à Deux” flopped. Director Todd Phillips, however, should take some consolation from the fact that his sequel/social experiment revealed the hollowness behind much of the hatred for the first film.

With Coppola, Quentin Tarantino, and John Waters in his corner, Phillips hardly needs my endorsement. I’m offering it anyway because of how devilishly he fulfills and fractures the demands of the Batman mythos, especially in the scene where Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix) sorrowfully declares, “There is no Joker.”

That’s the best line in the movie, even though Arthur is wrong. There is a Joker. His name is Luigi Mangione.

10.-12. “Sometimes I Think About Dying,” “Young Woman and the Sea,” and “Magpie”

Any young actor looking to succeed in post-pandemic Hollywood would do well to follow Florence Pugh’s playbook: play a B-list Marvel superhero, star in an A24 folk-horror flick, and always take Christopher Nolan’s call (even for a microscopic role).

Amid her post-“Star Wars” malaise, Daisy Ridley could have mimicked Pugh page-for-page. Instead, she burned a fresh path by starring in (and producing) a trio of dramas that took a blowtorch to contemporary cinematic trends.

In “Sometimes I Think About Dying,” Ridley plays a suicidal office worker living in Astoria, Oregon; in “Young Woman and the Sea,” she’s Trudy Ederle, the first woman to swim the English Channel; and in “Magpie,” she’s the deliciously Machiavellian mother of a child actress.

Each 2024 Ridley movie is a rebellious throwback. “Sometimes” has more in common with early Sofia Coppola than today’s indie films, “Sea” is unfashionably solid and sentimental, and “Magpie” is a “Basic Instinct”-style provocation (not the domestic dirge it was marketed as).

Paying tribute to her “Star Wars” character, Ridley once impishly said, “I’ll always be Rey.” But last year proved that Ridley, like any performer who commands our attention, will be whoever she wants to be.

Honorable Mentions: “Civil War,” “Conclave,” “Heretic,” “Immaculate,” “Juror #2” “Nightbitch,” “Sing Sing,” “2073,” “Twisters,” “Y2K”