In a world where ranking Tom Cruise’s “Mission: Impossible” haircuts is a minor sport, lists pose an existential threat to film criticism—according to the nonbelievers, at least.

You know who I’m talking about: The people who don’t rank the “Fast & Furious” films from best to worst while they’re stuck in traffic. The people who don’t dreamily contemplate 10 Reasons Why Wong Kar-wai’s Late Period Is Actually Awesome while dining on canned pineapple. The people who are, ya know, normal.

I am not normal—and I blame A.O. Scott. At 13, I devoured the former New York Times film critic’s 2004 top 10 list, which was bookended by “Million Dollar Baby” and “Fahrenheit 9/11.” I hadn’t seen either film, but I had begun to learn that to make a list of movies is to throw down a cinematic gauntlet. This is what matters to me. In this order. For these reasons.

At their worst, lists reduce cinema to banalities. (It’s atrociously reductive to call Terrence Malick’s quietly thunderous “A Hidden Life” the third-greatest film of 2019, even if it was.) At their best, lists remind us that film criticism is about the critic as much as the film, inviting us to humble ourselves by honestly expressing our deepest passions and prejudices.

The great critic Manohla Dargis once said that there are more important things than how a movie makes you feel. I agree, but critics too often present themselves as dispassionate jurors rendering judgment from on high. In truth, we are fickle, emotional beings searching for meaning in the subjective murk of art—and pretending otherwise does neither our readers nor our work any favors.

Thus, the following list is neither canon nor pantheon. It is simply me introducing myself to you. In time, I will revisit and expand it (ask me in five or 10 years if/where “Drive My Car” and “Top Gun: Maverick” fit in). For now, this is what matters to me. In this order. For these reasons.

25-23. The “Dark Knight” Trilogy

Many a tastemaker would have you believe that superheroes destroyed cinema by seducing moviegoers with fascist visions of strongmen whose heroism demands obedience. It’s a case that conveniently ignores an obvious truth: Superheroes aren’t above us. They are us.

So it is with Christopher Nolan’s Bruce Wayne, played as a boy by Gus Lewis (in 2005’s “Batman Begins”) and as a man by Christian Bale (in “Begins,” 2008’s “The Dark Knight,” and 2012’s “The Dark Knight Rises”). The first time we see him, he’s a child dashing through a verdant garden; the second time, he’s a hirsute inmate in a Bhutanese prison. How did he get there? And where will he go next?

The answers to those questions are often harrowing, especially when sadistic villains (like Heath Ledger’s Joker and Tom Hardy’s Bane) are involved. Yet through it all, there is Bruce’s humanity: his love for Alfred (Michael Caine), his faith in the goodness of Gotham’s citizens, and his tragic addiction to a cape and cowl that shield him from the ravages of grief.

“Look beyond your own pain,” Rachel Dawes (Katie Holmes) admonishes Bruce in “Begins.” He does, and so does Nolan, ending the trilogy not by wallowing in fury and cynicism, but with a heartfelt defense of heroism and romance. “You could’ve gone anywhere, been anything. But you came back here,” Selina Kyle (Anne Hathaway) tells Bruce as they weather the greatest of Gotham’s wars. “I guess we’re both suckers.”

22. “Blue is the Warmest Color”

If I (A) spoke French, (B) was independently wealthy, and (C) was friends with Adèle Exarchopoulos, I would bankroll a sequel to “Blue is the Warmest Color” (2013), Abdellatif Kechiche’s loose adaptation of Julie Maroh’s graphic novel. Why? Because the ending—Adèle (Exarchopoulos) lighting up a cigarette and leaving her ex-girlfriend’s art exhibit—is not enough for me.

To me, Adèle was never just a character. She was the girl who tearfully choked on a Butterfinger, showed up to school in an orange turtleneck, and danced to Lykke Li’s “I Follow Rivers” at a birthday party, waving her arms as if lost in a trance. She was so real that after three hours of heartbreak, I had to know that she was going to be okay.

Based on that ending—the mournful steel drum that plays over the film’s final shot reverberates with resignation, not hope—I’m not sure if she is. But despite the emotional wounds it inflicts on its audience, I am sure that when “Blue is the Warmest Color” was released, it was the movie I needed to see (though I recognize that the infamy that shrouds “Blue” is more important than my assessment of the movie’s artistic merit).

Two years before I bought a ticket to “Blue,” I fell in love. It was a one-sided romance with a friend, but at the time, it lacerated my heart more than any relationship with anyone I dated. Like Adèle, I was schooled in the reality that not loving what (or who) is good for you is thrillingly, terrifyingly easy.

“Blue” is not my story—it’s the story of a gay Frenchwoman who survives a traumatizing breakup and becomes a teacher in the city of Lille—but films can unite us with characters whose experiences we couldn’t otherwise comprehend. Maybe that’s the reason why whenever I wondered if Adèle was going to be okay, what I was really wondering was if I was going to be okay.

I’m still not sure about either of us, but I haven’t given up. I hope she hasn’t either.

21. “Two Lovers”

Leonard (Joaquin Phoenix) is dating Sandra (Vinessa Shaw). But when Michelle (Gwyneth Paltrow) tells him that she’s moving to San Francisco, his commitment evaporates. “Don’t go,” Leonard begs. “I love you. You may not want to hear it, but it’s true. I’m not a little kid! This isn’t some stupid fucking crush! You think I don’t know love?”

Whether Leonard knows love is debatable, but James Gray does. Under his direction, “Two Lovers” (2008) is not just a love-triangle movie; it’s a love movie. Gray has been married to documentarian Alexandra Dickson Gray for nearly 20 years, but like his former neighbor, Sofia Coppola, he remains a cinematic maestro of isolation and yearning.

I won’t presume to know what Gray has experienced, but I know what “Two Lovers” understands. It understands staring through a window at someone you long for. It understands making love and staggering home in jubilant disbelief. It understands buying plane tickets and an engagement ring, then dropping your travel bag into a darkened courtyard and dashing toward your imagined destiny.

Unlike Leonard’s fickle infatuations, my romance with Gray’s movies has endured since 12th grade. I was blissfully seduced by “We Own the Night” (2007), “The Lost City of Z” (2016), and “Ad Astra” (2019), though “Two Lovers” is my first love and my true love from his filmography, the high school girlfriend I have no desire to get over.

I’ve come to appreciate the tenderness of Leonard’s relationship with Sandra (her giving him a pair of leather gloves in a cafe is the most genuinely romantic moment in the movie). Still, I admire the purity of his misguided passion for Michelle, a gifted gaslighter who wields the phrase “I think if you knew me better, you wouldn’t feel that way” like a weapon.

“You think if I got to know you, I wouldn’t love you, but I do know you and I love you even more!” Leonard declares to Michelle. He’s wrong; she’s wrong; they’re wrong together. But maybe, if Leonard is lucky, he’ll grow up enough to share our compassion for the deluded kid he once was.

20. “Interstellar”

There is a moment in “Interstellar” (2014) when Cooper (Matthew McConaughey), an astronaut exploring a distant galaxy, returns to his ship to find 23 years of messages from his children. Frozen in time by his proximity to a black hole, Cooper is stranded in his forties—while his offspring have lived decades, aging from buoyant kids to anguished adults.

Murph (Jessica Chastain) is now a NASA scientist toiling on an Earth pummeled by agricultural blight; Tom (Casey Affleck) has fallen in love, mourned his grandfather, and buried his first son. “You aren’t listening to this, I know that,” Tom tells Cooper. “All these messages are just drifting out there in the darkness.”

Cooper is listening—and so is Christopher Nolan, who directed from a screenplay he wrote with his brother, Jonathan. Theirs is a movie that cares not only about the end of Earth and the search for a backup planet, but about porch chats, parent-teacher conferences, childhood toys, shattering farewells, and haunting homecomings. It is the story of who we may become and who we are now.

We are Murph, dutifully living up to the promise of our youth, and Tom, poignantly falling short. We are Cooper, eager for adventure, but blind to its cost. We are Dr. Brand (Anne Hathaway), professionally jaded, yet committed to the film’s creed: “Love is the one thing we’re capable of perceiving that transcends dimensions of time and space.”

“Interstellar” is a slower, stranger telling of the tale Nolan told in “Inception” (2010): a wayward father fights his way home. This time, however, the children are not faceless specters in dreams. Murph (who is played in later years by Ellen Burstyn) is thoroughly present, even when she reunites with Cooper before closing her eyes for the last time.

“No parent should have to watch their own child die,” she tells him. “I have my kids here for me now. You go.” Love transcends time, even as time takes its toll.

19-17. “To the Wonder,” “Knight of Cups,” and “Song to Song”

In Oklahoma, a couple clings to the dying breath of the romance they began in Paris. In California, a screenwriter wanders, seeking love with an actress, his ex-wife, a dancer, and a married woman. In Texas, a satanic executive befriends two naïve musicians, coveting and corrupting their bond.

These stories form Terrence Malick’s loose trilogy of contemporary romances, bound together not by narrative, but by style and theme. Gazing through a luminous haze, Malick bears witness to the seeming impossibility of true love in the modern world, surfing waves of desire and despairing at the emptiness left in their wake.

Even among many Malick acolytes, “To the Wonder” (2012), “Knight of Cups” (2015), and “Song to Song” (2017) are regarded as peculiar afterthoughts in the director’s mythic career. To me, they are not just thoughts, but the thoughts. I was 22 when the trilogy began and 26 when it ended—and just as the films understood me, I understood them.

I got why the Oklahoma couple (Olga Kurylenko and Ben Affleck) clung to a memory of romance instead of romance itself; why the screenwriter (Christian Bale) searched for love but rarely found it; why the musicians (Rooney Mara and Ryan Gosling) got caught in the crosshairs of fulfillment and ambition, surviving with wounds that left them no choice but to mature.

“They say follow the light,” Gosling’s character says. “How do you? When you’re young, it’s not easy to know what is the light.” To Malick, the light is God, but his trilogy is spiritual in a way that doesn’t dismiss secular moviegoers. These films, I suspect, are the creation of a devout artist who believes that God belongs to everyone, not just those who pray in His name.

Throughout the trilogy, the human and the divine intersect, like when Kurylenko and Affleck bounce on the shore by Mont Saint-Michel or when Bale’s purple shirt ripples in a desert breeze. “So much love inside us…that never gets out,” the screenwriter whispers. It is Malick who brings it out, using the world around him to express the feelings that his characters struggle to contain.

In his review in The Independent, Christopher Hooton wrote that “Song to Song” is “suffused with that feeling of when you want to cry but can’t.” That’s true of the entire trilogy—and it’s why, whenever I proclaim my love for these movies, I always return to the words Mara speaks as “Song to Song” ends: “This. Only this.”

16. “Star Trek”

I knew nothing about warp drive or the Prime Directive when I first watched J.J. Abrams’ fiery 2009 remix of Gene Roddenberry’s utopian mythology. But I didn’t need to know; I needed to weep. And weep I did as George Kirk (Chris Hemsworth) sacrificed himself to save his wife and his newborn son, uttering one last “I love you” before he turned to cosmic ash.

That scene, which opens the movie, is a transcendent symphony of love and loss; it’s almost a letdown that what follows is only (only!) a supremely moving and rousing adventure. Yet the screams of Winona Kirk (Jennifer Morrison) as George meets his fate echo into the void and throughout the film, injecting Abrams’ prequel with blazing poetry.

For some moviegoers, including Nicholas Meyer, director of “Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan” (1982), the blaze was too ferocious. “I don’t understand Spock going around slugging people,” he told trekmovie.com in 2014, presumably alluding to the scene where James T. Kirk (Chris Pine) goads Spock (Zachary Quinto) in the wake of tragedy (“You feel nothing! It must not even compute for you!”).

Time has a way of transforming heresy into orthodoxy; Meyer missed the irony that he was once a young rebel who allowed an ultra-logical Vulcan to tear up at Spock’s funeral. And just as “Star Trek” needed Meyer in 1982, it needed Abrams in 2009—for his steadfast idealism, his defiant nostalgia, and his heartfelt depiction of Starfleet officers forged by desperation, duty, and grief.

Now that I’m enough of a Trekker to pontificate about Ferengi politics, I will concede that Abrams’ “Trek” lacks the allegorical ambition of its television progenitors. Still, I remain awed by the wit and soulfulness he brought to Roddenberry’s galaxy, especially in the scene where a bloodied Kirk casually plays with a starship-shaped salt shaker, toying with his expected destiny.

He could go places, that dude, if he would just get his shit together. And he will.

15. “La La Land”

A man in a dark suit walks away from a piano. A woman in a blue dress walks up to him. “I just heard you play….” she begins. Before she can finish, he kisses her, unleashing a dream of the life they might have had: the Parisian sojourn they might have taken, the home they might have lived in, the child who might have been theirs.

Mia (Emma Stone) and Sebastian (Ryan Gosling) are long separated; what we see is a vision of the romantic road not taken. And on the night I first saw “La La Land” (2016), the third film from writer-director Damien Chazelle (“Babylon,” “First Man”), I willed it to be real, infuriated by the injustice of two people sharing such explosive chemistry and not spending the rest of their lives together.

The romance commences with a bout of road rage on a steaming Los Angeles freeway, but the film’s exuberant musical numbers gradually bring Mia, an actress, and Sebastian, a jazz pianist, closer together. With “Another Day of Sun,” they meet; with “Mia & Sebastian’s Theme,” they touch; with “A Lovely Night,” they bond. “And maybe this appeals/To someone not in heels,” Mia sings. Soon after, the high heels come off.

By the end of the first act, Mia and Sebastian are literally ascending to the heavens in the Griffith Observatory. Beaming and waltzing through a starry blue expanse to the beat of Justin Hurwitz’s soaring score, they would probably be ecstatic if the movie ended there. If only.

Believing that Sebastian’s scheme to open a jazz club is incompatible with Mia’s pursuit of a role in a Paris-set film, the couple ultimately break up at Griffith Park, far above a city that once gleamed with possibility. “When you get this, you gotta give it everything you got,” Sebastian tells Mia. “Everything. It’s your dream.”

A.O. Scott wrote that “La La Land” was “a careerist movie about careerism,” and he wasn’t wrong: Mia and Sebastian sacrifice their relationship at the altar of ambition. Scott also wrote that there is a difference between what a movie is “about” and what it “is”—which explains why “La La Land” is about the end of a romance and is one of the most romantic movies ever made.

It isn’t just that Stone and Gosling are even more swoon-worthy together than they were in “Crazy, Stupid, Love” (2011); it’s that Chazelle embraces the romance of self-love. In the final scene, Sebastian is left sitting alone at the piano after he and Mia share a last look from across his crowded club, and rather than wallow in her departure, he counts off: “One, two. One, two, three, four.” The show must go on.

14. “The Fountain”

From the ballerina mutilation in “Black Swan” (2010) to the baby sacrifice in “mother!” (2017), Darren Aronofsky has been terrorizing moviegoers for over a quarter of a century. Yet his desire to move us is stronger than his hunger to provoke us—especially in “The Fountain” (2006), a film so formally innovative that it left 16-year-old me overwhelmed by a single thought: I didn’t know you could do that.

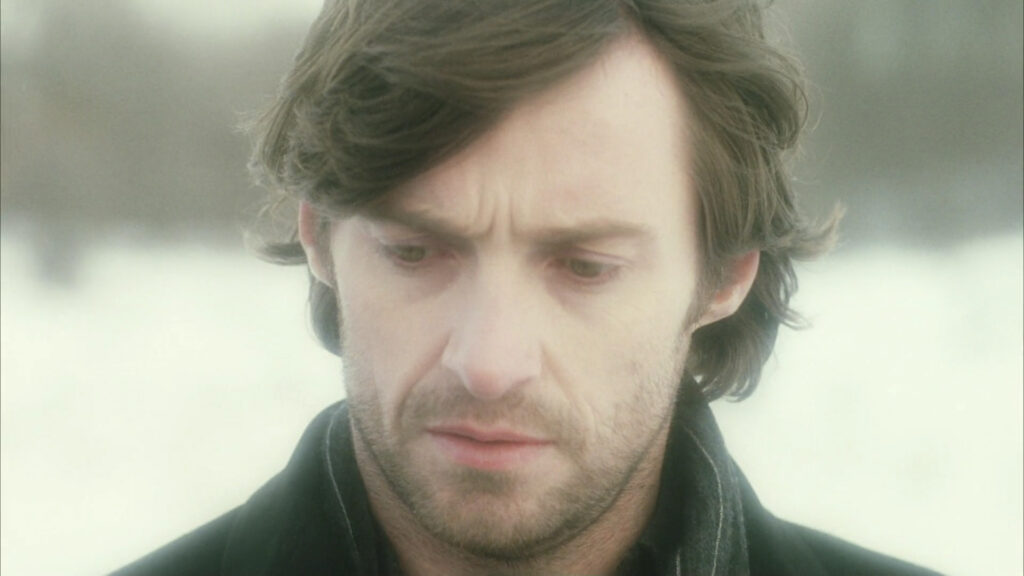

“The Fountain” is about three men, each played by Hugh Jackman. He’s a conquistador searching for the Tree of Life; a scientist seeking a cure for his wife’s brain tumor; and an astronaut drifting toward a dying star, haunted by his long-dead love (Rachel Weisz, who plays each Jackman-portrayed character’s paramour).

While my favorite storyline is the conquistador’s—it’s divine to watch him kneel before his Queen in a hall of suspended lamps—it is the present-day scenes that crystalize Aronofsky’s moving disdain for the pursuit of immortality.

“I want you to be with me!” the scientist cries as his wife, Izzi, implores him to accept her imminent death. “I am with you,” she declares. “Look!” Each day he spends chasing the myth of a miracle cure for her illness is a wasted day he could have spent loving her—a truth he can’t comprehend until he’s alone in the bedroom they once shared, weeping as snow falls outside.

“I think [that scene] makes a lot of people uncomfortable, because it’s rare you see a man cry on film, especially a man cry over love,” Aronofsky opined in his director’s commentary. “And it’s a shame that that type of sentimentality is not represented in film.” It’s a sentimentality he commits to with reckless, heroic abandon, leaving toxically masculine tropes in tatters.

Aronofsky eventually unites the three stories of “The Fountain” in a narrative Möbius strip that leaves you in blissful awe of cinema’s possibilities, but he never forgets what the film is about: a man who loses his wife. “Bye, Izz,” the scientist whispers after he plants a seed at her grave. Finally, he gets it: To embrace the inevitability of death is to live. And to love.

13. “Inception”

Admit it: The top wobbled. For years, cynics have insisted that the long-spinning silver top at the end of Christopher Nolan’s “Inception” meant that Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) didn’t return home to his children, James and Phillipa—that his homecoming was merely the fantasy of a father forever lost in his dreams.

To quote Nolan’s idol, George Lucas: I don’t like that and I don’t believe that. (And not just because the top obviously—obviously!—wobbles before the end credits roll.) “Inception” defends dreaming as a vital, reverberant part of our lives, but Nolan wants us to wake up, even if it means walking away from his fiendishly entertaining film.

That truth is frequently lost on Cobb and his squad of dream navigators, who have been hired to invade the mind of troubled tycoon Robert Fischer (Cillian Murphy). Their mission? Devise a dream that persuades Fischer to split up his late father’s energy conglomerate, a task that requires the team to employ the empathy of artists and the deviousness of spies.

“We suggest breaking up his father’s company as a ‘screw you’ to the old man,” Eames (Tom Hardy) proposes. “No, because I think positive emotion trumps negative emotion every time,” Cobb replies, sounding like a filmmaker pitching a happy ending to a doubtful crew. “We all yearn for reconciliation. For catharsis.”

For Cobb, catharsis proves elusive. If he successfully dupes Fischer, he’ll be cleared of a bogus murder charge that has kept him estranged from his children, but does he want to return? Or does he want to surrender to Mal (Marion Cotillard), a specter of his late wife who oozes through his subconscious, tempting him to abandon his waking life?

In “Following” (1998) and “Memento” (2000), Nolan’s dreamers were consumed by their delusions, unable or unwilling to see where truth ended and lies began. By contrast, “Inception” shakes off the punkish nihilism of his early works, proclaiming that we have a moral duty to escape the comfort of our own minds for the sake of the people who need and love us.

When Cobb admonishes Mal’s apparition—“You’re just a shade of my real wife”—it’s as if Nolan were acknowledging the limits of cinema. Much as Mal is a mere shade of the woman Cobb loved, movies are a mere shade of our existence. “Inception” just happens to be a particularly vibrant shade, sharpened by the joy of Joseph Gordon-Levitt dashing across hotel ceilings and Hardy daring us to dream a little bigger (darling).

“I miss you more than I can bear,” Cobb tells Mal. “But we had our time together. And I have to let you go. I have to let you go.” Neither a dream nor a film—even a film by Christopher Nolan—is a substitute for a life well lived.

12. “The Dreamers”

In “The Dreamers” (2003), Matthew (Michael Pitt) and Theo (Louis Garrel) are two points of a love triangle, but their first battle is fought over whether Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin reigns supreme. The winner? Theo, who triumphs with his rapturous tribute to the last shot of Chaplin in “City Lights” (1931).

“He looks at the flower girl, she looks at him,” Theo says with wonder. “And don’t forget she’s been blind, so she was seeing him for the very first time. And it’s as if, through her eyes, we also see him for the very first time. Charlie Chaplin, Charlot, the most famous man in the world! And it’s as if we’ve never really seen him before.”

Those aren’t the words of a fan—they’re the words of a fanatic. Written by Gilbert Adair and directed by the deceased but perennially controversial Bernardo Bertolucci, “The Dreamers” conveys the religious fervor that cinema can awaken in our souls, a feeling at once exhilarating and oppressive. “Maybe, too, the screen really was a screen,” Matthew muses. “It screened us from the world.”

The world of “The Dreamers” is Paris, circa 1968, though the historic political activism of the period is of middling interest to Theo and his twin sister, Isabelle (Eva Green). They’re too busy seducing Matthew, a naïve American student, into their private universe of cinema worship and kinky provocations. “You barely even know me,” Matthew says when he’s invited to live with them. “This way we get to know you,” Theo replies.

For Matthew, getting to know the twins is joyous—Isabelle, dancing in sunglasses and white overalls, c’est magnifique!—and disturbing. He freaks when he spies Theo and Isabelle sharing a bed, and ickier indiscretions follow, like the nighttime ordeal that could be politely described as “the kitchen scene” (and impolitely described as the scene with the fried eggs, the attempted rape, and the blood on Michael Pitt’s lips).

Despite being based on the late Adair’s 1988 novel “The Holy Innocents,” “The Dreamers” demolishes the book’s plot, ditching a pointless sojourn to the French countryside and an insufferably treacly conclusion. What remains is an operatic chamber piece, set mostly in the twins’ apartment, about a ménage à trois that is at once disgusting, poignant, and hilarious.

“You’re both fucking crazy!” Matthew roars at the twins. He’s right, but he’s addicted to their craziness because he understands it. Even as Matthew chides Theo and Isabelle for “clinging to each other,” he clings to them with equal ferocity, hoping that the three of them can hold back the tide of adulthood by drowning themselves in their shared passion for movies and sex.

The first time I saw “The Dreamers,” I was so shocked that I thought I hated it. But shock is a distortion of sense, and once it wore off, I understood that Bertolucci had unleashed something beautiful: a movie about loving people until the moment when you’re forced to accept that it is beyond your power to close the distance between you and them.

That moment arrives when Matthew struggles to stop Theo from hurling a Molotov cocktail during a protest. “We do this! We use this!” he cries to the twins, kissing them both. He’s right, but not for them; he can either let them go and live, or follow them and burn. Theo and Isabelle, the most important people in his life. And it’s as if he’s never really seen them before.

11. “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy”

The extraordinary story of “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” (2005) begins with a wholly remarkable book written in 1979 by the late Douglas Adams, an Earthman. It was a delightful tale—so delightful that 20 years ago, one might have greeted the possibility of a film adaptation with cheery responses like “unfilmable” and “suicide mission.”

Though making such a movie seemed akin to guzzling a Pan Galactic Gargle Blaster while reading Vogon poetry, a music video director named Garth Jennings, who had never helmed a feature film, was enticed. One presumes that he was intimidated by Adams’ legacy, but relieved that he wouldn’t have to depict the globbering mattresses of Sqornshellous Zeta (which do not appear until book four).

While Adams wrote that humans are Earth’s third-most intelligent species, Jennings’ actors had more wit than most. There was Martin Freeman (strangely handsome in a lumpy green bathrobe); Sam Rockwell (talked like W., walked like a Christian hippie); Zooey Deschanel (cosmic pixie dream girl, not yet a singer of beautifully depressing Christmas covers); and Yasiin Bey (then called Mos Def, but a comic deity no matter his name).

Like most worthwhile films, “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” kicks into high gear with a dolphin singing, “If I had just one last wish/I would like a tasty fish.” Any doubts that Jennings could maintain the sublime silliness of Adams are subsequently quashed by the director’s affinity for delectable background gags (a square-wheeled bicycle!) and his deft handling of Vogon lunch orders (“I think I’ll have soup today”).

Of course, like all great comedies, this one is secretly a drama. Jennings mixes melancholy and wonderment—the sight of Marvin (the miserable android voiced by the much-missed Alan Rickman) alone at sunset is as haunting as it is heavenly—without forsaking the teachings of Slartibartfast (Bill Nighy), who stumbles into the film to preach that “the only thing to do is say hang the sense of it and keep yourself busy.” Amen.

Slatibartfast’s wisdom likely served the cast and crew of “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” well after the movie received a poor score from a produce company called Rotten Tomatoes (though what fruit has to do with moving pictures remains a mystery). And as for sequels, it may have been a deliberately ill omen when the film ended with its heroes making a wrong turn on their way to the Restaurant at the End of the Universe.

Nevertheless, “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” did what most movies aspire to and nearly all movies fail at: It made a few people happy. That includes a film critic foolhardy enough to imitate Adams’ writing style (though this reviewer hopes his effort is slightly less irksome than other critics’ attempts to emulate the likes of Jane Austen, Jonathan Swift, and Dr. Seuss).

But enough blabbering. The Restaurant at the End of the Universe awaits, and I’ve reserved a table. I’m hoping to run into some old friends.

10. “Titanic”

If you’re cool, your favorite James Cameron film is probably the one with “You’re terminated, fucker!” or “Get away from her, you bitch!” As I am not cool, my favorite Cameron film is the one where Kate perches with Leo on the bow of the world’s most beautifully doomed ship and cries, “Jack! I’m flying!”

Manohla Dargis wrote that “Titanic” (1997) was a “megamelodrama,” but that could describe all of Cameron’s films. Melodrama sprouted as early as “The Terminator” (1984) when Kyle Reese (Michael Biehn) professed, “I came across time for you, Sarah,” and it blossomed in “Aliens” (1986) when Hicks (Biehn) told Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) that giving her a locater didn’t “mean we’re engaged or anything” (it totally did).

In “Titanic,” Cameron’s penchant for the mega and the melodramatic reaches its zenith through delayed gratification. Flickers of the past—a lock of blond hair falling over a young man’s eyes, a servant opening a door—gradually pierce the present, leading to our glorious first glimpse of what Titanic survivor Rose (Gloria Stuart, who died in 2010 at age 100) calls “the ship of dreams.”

To recreate the ship of dreams, Cameron created the movie of dreams. When Jack (Leonardo DiCaprio) first glimpses a younger Rose (Kate Winslet), she stands on a precipice above him, as radiant in sunlight as Juliet was in moonlight. “You’d as like have angels fly out your arse as get next to the likes of her,” warns Tommy Ryan (Jason Barry), but like Cameron, Jack is a believer.

I became a believer 10 years ago, when I first watched “Titanic” at a beach house in Manzanita. Jamming the movie into the DVD player, I anticipated a feast of laughable sappiness, but swiftly ascended into a state of rapture, overwhelmed by the sight of dolphins leaping out of the Atlantic and the sound of James Horner’s pulsating, wonderstruck score.

Wonder turned to horror as I watched the ocean swallow the great ship whole, along with its passengers—the cowardly and the noble, the guilty and the innocent, the rich and the poor. “Three years I’ve thought of nothing except Titanic, but I never got it,” present-day treasure hunter Brock Lovett (Bill Paxton) admits. “I never let it in.” With Cameron directing, not letting it in was never an option.

Both onscreen and off, “Titanic” is a reminder that death comes for us all. In the years since its release, James Horner was killed in a plane crash, Bill Paxton suffered a fatal stroke, producer Jon Landau died of cancer, and Will Jennings (the lyricist who wrote “My Heart Will Go On” with Horner) passed away.

Cameron, meanwhile, goes on; post-“Titanic,” he made two “Avatar” films, and he has three more to go. I’m a fan of that franchise, but I suspect that he peaked with “Titanic.” Like “The Fountain,” it’s a movie that embraces its own mortality, and that means there can be no sequels. There can only be the people who loved—sincerely, ferociously—as the ship surrendered to the waiting depths.

9. “X2”

“How does it look from there, Charles?” Magneto (Ian McKellen) asks Charles Xavier (Patrick Stewart), his old frenemy and fellow mutants’ rights activist. “Still fighting the good fight? From here, it doesn’t look like they’re playing by your rules. Maybe it’s time to play by theirs.”

In principle, “X2” (2003) is an Xavier movie; in temperament, it is a Magneto movie, exploding with blood and despair. Fighting the good fight, it turns out, sounds reasonable until soldiers arrive under night’s cloak, shattering windows and shooting children with tranquilizer darts.

In “X-Men” (2000), Xavier and Magneto clashed over how to confront the rise of anti-mutant bigotry. Xavier’s tolerance helped smother the draconian Mutant Registration Act, but Magneto wasn’t mollified. “Doesn’t it ever wake you in the night,” he wondered menacingly, “the feeling that someday they will pass that foolish law, or one just like it, and come for you?”

Magneto’s words are made manifest in “X2”: The military invades Xavier’s School For Gifted Youngsters, leaving its students and instructors vulnerable to the genocidal William Stryker (Brian Cox). “It’s time,” Stryker says. “Time to find our friends.” As spoken by Cox, those words are more sickening than any violent threat.

While “X2” is based on the 1982 graphic novel “God Loves, Man Kills,” it is a cinematic child of several movie sequels. Like “Aliens,” it subjects its heroes to a metal-and-concrete labyrinth; like “Terminator 2: Judgment Day” (1991), it features an entertaining alliance with a former adversary; and like “The Wrath of Khan,” it climaxes with an apocalyptic sacrifice.

In the wake of that loss, Scott (James Marsden) bawls in movingly unmanly fashion, Logan (Hugh Jackman) keeps numbly repeating, “She’s gone,” and Nightcrawler (Alan Cumming) finds solace in his faith. “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of the death, I will fear no evil, for thou art with me,” he recites, more out of hope than belief.

“X2,” which was directed by the now-disgraced Bryan Singer, nods to future sequels, yet feels like an ending. So shaken by grief are its characters that they stand around dumbly—with the exception of Xavier, who gently gets back to work. “Now, tell me,” he queries his students, “have any of you read a book by an English novelist named T.H. White called The Once and Future King?”

Battle lines are drawn, wars are fought, lives are lost. That’s no reason to dismiss the class.

8-6. The “Star Wars” Trilogy

In 2017, George Lucas proclaimed “Star Wars” to be “a film for 12-year-olds.” He was playfully trolling older fans like me, but he was also underestimating his own creation. “Star Wars” is for 12-year-olds and who they become: defiant idealists like Luke Skywalker, wavering cynics like Han Solo, wounded philosophers like Yoda, and conflicted tyrants like Darth Vader.

The end of childhood has long obsessed Lucas. In “American Graffiti” (1973), he conjured up a night of cruising in Modesto, California, circa 1962, evoking an innocence later eroded by the quagmire of Vietnam and the skullduggery of Nixon. The movie served up a world of cars, girls, and good vibes—a world that was poignantly entertaining because it had ceased to exist.

Like many of the kids in “American Graffiti,” Luke (Mark Hamill) is ravenous for adventure, and his hunger rises early in “Star Wars: A New Hope” (1977). “Luke’s just not a farmer, Owen,” Aunt Beru (Shelagh Fraser) tells Uncle Owen (Phil Brown). “He has too much of his father in him.” “That’s what I’m afraid of,” Owen replies grimly.

With its galactic feats of derring do (save the princess, blow up the Death Star!), “A New Hope” plays like one of Luke’s childhood dreams—dreams that curdle in “The Empire Strikes Back” (1980) as he emerges from hyperspace, coming down to swampy, murky earth. “Adventure, heh. Excitement, heh. A Jedi craves not these things,” Yoda (Frank Oz) scoffs. “You are reckless.”

“Star Wars” is adventurous, exciting, and reckless. It’s “Use the Force, Luke” echoing along the Death Star’s canyons. It’s stormtroopers firing blasters to the rhythm of John Williams’ score. It’s Luke and Leia (Carrie Fisher, R.I.P.) rocketing through the forests of Endor on speeder bikes, the passing trees reduced to a single emerald blur.

And yet as we grow, “Star Wars” grows with us. Just as “New Hope” captures the simplicity of childhood and “Empire” embodies the angst of teendom, “Return of the Jedi” (1983) chronicles Luke’s entry into adulthood—a transition marked by his quest to save the soul of his wayward father, Vader (who has the towering body of David Prowse and the magnetic voice of James Earl Jones, both of whom have since become one with the Force).

“Luke, you’re going to find that many of the truths we cling to depend greatly on our own point of view,” Ben Kenobi (Alec Guinness) says gravely. Luke clings to the belief that his father is redeemable—and he’s willing to die for it. “I’ll never turn to the dark side,” he declares, doffing his lightsaber and facing the Emperor (Ian McDiarmid). “You’ve failed, your highness. I am a Jedi, like my father before me.”

When I graduated from high school, I had those words printed below my yearbook portrait. I had accrued plenty of “Star Wars” paraphernalia by then—including my homemade Boba and Jango Fett costumes—but the most precious collectable I ever possessed was Luke’s rejection of the false choice between joining his father or killing them.

I could have grown up with a pop myth about heralded heroes and vanquished villains. Instead, I came of age with the work of Lucas and his coconspirators (including those who have passed on, like “Empire” director Irvin Kershner and “Jedi” director Richard Marquand). Together, they preached the high power of compassion and forgiveness within the secular spirituality known as the Force.

“For my ally is the Force,” Yoda told us. “And a powerful ally it is. Life creates it. Makes it grow. Its energy surrounds us and binds us. Luminous beings are we, not this crude matter!” On terra firma, “Star Wars” and its fans have not always lived up to those teachings. Yet at its best, Lucas’ galaxy far, far away makes luminous beings of us all.

5-3. The “Spider-Man” Trilogy

“This, like any story worth telling, is all about a girl,” Peter Parker (Tobey Maguire) tells us at the start of “Spider-Man” (2002). “That girl. The girl next door. Mary Jane Watson.”

You could chock that introduction up to the modesty of a working-class kid from Queens, but Peter isn’t wrong. Sam Raimi’s “Spider-Man” trilogy is both the story of a superhero and the story of the woman he loves—from the day six-year-old Peter first glimpses Mary Jane to their poignant last dance in a Manhattan jazz club.

When it comes to Stan Lee superheroes adapted for screen, Raimi’s Spider-Man is my Mary Jane. In 10th grade, my ex-girlfriend asked if the numbers scrawled in my planner were a countdown to the last day of school; I explained (much to her amusement) that they were, in fact, my countdown to the release of “Spider-Man 3” (2007). Daylight saving came and went, but I always set my watch to Spidey time.

Raimi and I have that in common. A devout fan, he grew up with a painting of Spider-Man on his bedroom wall, though it was helming the superhero-ish “Darkman” (1990) and moralizing dramas like “A Simple Plan” (1998) that primed him to be a Spidey wrangler.

Spider-fans love sparring over the amazingly irrelevant, like mechanical versus organic web shooters and the appropriate number of wisecracks when battling the Hypno-Hustler. Raimi realized that only one tenet of Spidey mythos is truly sacrosanct: that Uncle Ben (Cliff Robertson, who died in 2011) is dead and that Peter Parker is to blame.

“Uncle Ben was killed that night for being the only one who did the right thing,” Peter tells Aunt May (Rosemary Harris) in “Spider-Man 2” (2004). Peter didn’t pull the trigger, but in Raimi’s telling, his greed and lust helped load the gun. His self-inflicted punishment? Donning a costume that divides him from the world (and, Peter confesses, “rides up in the crotch a little bit”).

Unlike the contemporaneous “Superman Returns” (2006), the “Spider-Man” trilogy honors its comic-book icon without ossifying him. Raimi ruthlessly tested Spidey’s moral authority and his own interpretation of the character, especially when it came to Peter’s vow to protect Mary Jane (Kirsten Dunst) by denying his love for her.

“I know you think we can’t be together, but can’t you respect me enough to let me make my own decision?” Mary Jane asks. “I know there’ll be risks. But I want to face them with you. It’s wrong that we should only be half alive, half of ourselves.”

As a Spidey auteur, Raimi’s work was always fully alive, even at its most embattled. The infuriatingly underrated “Spider-Man 3″ (Raimi himself called it “awful”) features some of his most kinetic and provocative filmmaking, especially in the notorious dance scene where a drugged-up Peter dazzles clubgoers with his superheroic foot work, then horrifies them with his drunken wrath.

Like “Star Wars,” the “Spider-Man” trilogy is a plea for empathy, with Raimi presenting a Peter who is as tainted as his enemies. “I did a terrible thing to you, and I spent a lot of nights wishing I could take it back,” says Flint Marko (Thomas Haden Church), the man who shot Uncle Ben. “I’ve done terrible things, too,” Peter tells him. It takes a sinner to forgive a sinner.

In 2010, Raimi quit “Spider-Man 4,” exasperated (according to Mark Edlitz’s book “Movies Go Fourth”) with the meddling of Sony Pictures. I was despondent at his departure—until, that is, I learned that the fourth film likely would have shattered Peter and Mary Jane’s romance, clearing the way for a Catwoman-esque character envisioned for Angelina Jolie.

Mary Jane’s identity is as multifaceted as Peter’s: She’s the daughter of an abusive home, an acclaimed off-Broadway star, a depressed singing waitress. Through it all (and thanks to the fourth film’s timely demise), the bond between her and Peter endures, right up to the final scene where he wordlessly asks her to dance in “Spider-Man 3.”

In “Spider-Man,” Peter tells Mary Jane that when he’s with her, he knows “what kind of man” he wants to be. The reality is more complex. Peter knows what kind of man he wants to be not only because of Mary Jane, but because of Uncle Ben, Aunt May, and the people of the city he serves. His connection to the anonymous New Yorkers he rescues may be somewhat intangible, but it is no less meaningful than his ties to his loved ones.

“He’s just a kid,” says a stunned train passenger (Tony Campisi) when he witnesses Peter unmasked in “Spider-Man 2.” “No older than my son.” In the end, we’re all just kids wearing masks. The most heroic thing about Spider-Man is that he finds the courage to take his disguise off.

2. “Metropolitan”

Late in “Metropolitan,” Tom Townsend (Ed Clements) and Charlie Black (Taylor Nichols) listen to a well-dressed stranger (Roger W. Kirby) reminisce at a bar about his vanished friends.

“You go to a party, you meet a group of people, you like them and you think, ‘These people are going to be my friends for the rest of my life,’” the stranger says wistfully. “Then you never see them again. I wonder where they go….”

Where do they go? “Metropolitan” has answers. Some people you meet get sober. Some date slimy music producers. Some are slain by stepmothers of “untrammeled malevolence.” An audacious few empty their wallets for a cab ride to the Hamptons, determined to rescue Jane Austen fans led astray by the titled aristocracy (who are “the scum of the Earth”).

To quote Nick Smith (Chris Eigeman), I’m not entirely joking—and neither is Whit Stillman. “Metropolitan,” his 1990 directorial debut, features high-class buffoonery so hysterical that it’s easy to overlook the coming-of-age saga unfolding during formal dances, endless afterparties, and ironic games of bridge.

“This is about the only economical social life you’re going to find in New York,” Nick tells Tom, reveling in the Christmas splendor he and his fellow New York preppies enjoy. “Music, drinks, entertainment, hot, nutritious meals—all at no expense to you.”

Tom isn’t so sure. The son of a moneyed father and a middle-class mother, he rants against the posh to conceal his insecurity about his “limited” resources and talks up the 19th century French socialist Charles Fourier to burnish his anti-bourgeois bona fides.

“It’s a bit ridiculous for someone to say that they’re morally opposed to deb parties and then attend them anyways,” Charlie says indignantly. “Well, I think it’s justifiable to go once to know firsthand what it is you oppose,” Tom replies. As spoken by Clements (who went on to become a pastor), this hypocrisy sounds hilariously reasonable.

An interloper in the prestigious clique known as “the Sally Fowler Rat Pack,” Tom is eagerly embraced by Nick, who schools him in the ways (according to him) of a modern bourgeois gentleman: top hats, detachable collars, and chivalry toward debutantes.

“I’m not sure if you realize this, but these girls are at a very vulnerable point in their lives,” Nick says somberly. “All of this is much more emotional and difficult for them than it is for us. They’re on display.” Part sarcasm, part paternalism, part genuine compassion, Nick’s creed is a testament to the wit, nuance, and feeling of Eigeman’s acting and Stillman’s writing.

In “Metropolitan,” Stillman mastered the art of writing “mildly deluded” nice guys. These young men are never as intelligent or as dignified as they believe, but they are downright heroic compared to bullies like Rick Von Sloneker (Will Kempe), a literal baron (and sexual predator) who loves to snap, “You really take that sort of thing seriously?”

“Metropolitan” is partially the story of Nick being cast out of the Rat Pack, an exile sealed with the film’s most poignant shot: Eigeman, dressed in a tux, waving farewell at Grand Central Station. Yet it is also the story of Tom and Charlie taking up Nick’s mantle of charmingly pompous decency, mainly by mounting a delightfully ill-advised mission to Rick’s home in the Hamptons.

Ostensibly, the purpose of this expedition is to “rescue” Audrey Rouget (Carolyn Farina), Tom and Charlie’s mutual crush, from Rick’s vulgar domain. That Audrey doesn’t need rescuing is beside the point; the boys want to play hero, and their attempt is absurdly touching.

I won’t tell you what happens when Tom and Charlie arrive at Rick’s house. I won’t tell you what makes Tom exclaim, “Jesus! That bastard!” I won’t tell you about the toy (or is it?) gun. I won’t tell you the context of the line “I warn you! He’s a Fourierist!” I won’t tell you what Tom and Audrey say on the beach as they stare at the horizon and the maw of adulthood.

All I will tell you is that in their own bumbling, beautiful way, Tom, Charlie, and Audrey grow up. “Metropolitan” ends with them attempting to hitchhike back to the Big Apple, only to find that no one will give them a ride. So they do what they have to do. They start walking.

1. “Lost in Translation”

It’s nighttime in Tokyo. In the back of a car, a man awakens and beholds the city around him, a vortex of sleek surfaces and gleaming lights. But by the time he reaches his hotel, the power of the future-shock architecture is overshadowed by a message from his wife: “You forgot Adam’s birthday. I’m sure he’ll understand.”

In another part of the hotel, a woman sits on a windowsill while her husband sleeps. She wakes him, but mere seconds pass before he resumes his slumber and his snoring. So the woman sits up, her features set in an unusual expression—a hazy, serious look for which a proper word has yet to be invented.

What the woman on the windowsill and the man from the car don’t realize is that this is no ordinary night. They don’t know that this is the start of a journey as towering as Tokyo’s skyscrapers. They don’t know that their lives are about to change. And neither did I.

I was 14 when I first saw Sofia Coppola’s “Lost in Translation” (2003), and I was a reluctant viewer—an action-obsessed teenager who would have rather been watching, God help me, “Attack of the Clones.” (I had not yet realized that any movie pairing Hayden Christensen with Natalie Portman belongs in the spice mines of Kessel.)

Yet as I was immersed in Coppola’s luminescent mood piece, I felt enraptured and terrified. What Bob Harris (Bill Murray) and Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson) were to each other (aside from fellow guests at Park Hyatt Tokyo) wasn’t clear, but I couldn’t bear the idea of them parting.

“Lost in Translation” has been called an unconsummated romance, which never felt right. It’s not about a purely platonic friendship (“friends” don’t typically watch “La Dolce Vita” on TV together in the middle of the night), but words like “friendship” and “romance” are too diminutive to evoke what Charlotte and Bob share.

Would a middle-aged movie star befriend an unemployed philosophy grad stateside? Doubtful. But when Bob and Charlotte meet in “Lost in Translation,” they are both Americans in an unfamiliar city and they are both profoundly lonely—especially since Bob’s once-fulfilling marriage is crumbling and Charlotte feels suffocated by her husband (a faithless, egocentric photographer played by Giovanni Ribisi).

Coppola knows there are far worse things than loneliness (in her ethereal 1999 feature debut “The Virgin Suicides,” togetherness equalled imprisonment). She also understands that isolation can hollow you out, making you feel pointless and worthless. That’s how Charlotte and Bob feel, and that’s why the power of their bond is amplified. It isn’t just a relationship; it’s a reprieve, just as my relationship with “Lost in Translation” has sometimes been.

There are those who believe that finding a favorite film is like getting married: However happy you may think you are, there’s always the option of divorce. I don’t think it works like that, at least not for me. I believe that choosing one movie you adore above all others is like finding your true love. It’s destiny, and destiny doesn’t have to be fully understood.

That’s why I have rarely wanted to know what Bob whispers to Charlotte in the movie’s famed final scene (which was shot at Shinjuku Station’s west exit). What matters is that through an embrace we clearly see and words we can’t quite hear, he and Charlotte manage to express what they mean to one another.

In other words, it’s a rejuvenation, not a farewell. When Bob sits in the backseat of his car and calmly tells his chauffeur to drive on, he’s no longer hiding beneath his usual blanket of deadpan self-pity, just as Charlotte isn’t alone on the windowsill anymore. The last time we see her, she’s striding purposefully down a crowded street, the beat of the Jesus and Mary Chain’s “Just Like Honey” giving weight to her every step.

In my own life, I’m not quite there, but I’ve held onto the hope embodied by the night Bob and Charlotte join Charlie (Fumihiro Hayashi) for karaoke. Charlotte sings “Brass in Pocket” (she does want some of Bob’s attention), while Bob goes for Roxie Music’s “More Than This”: “You know there’s nothing/More than this/Tell me one thing/More than this/Oh there’s nothing.”

Unlike Charlotte and Charlie, Bob is old enough to know that there really is nothing more than this—nothing more than connecting with other people when you least expect it and finding a window into their lives. Those moments can seem few and far between, but there will always be another karaoke night; you just have to be ready for it. To have faith in the idea of a karaoke night.

I do, just as I believe in the promise of that whisper and the promise of the last shot in “Lost in Translation”: Bob’s car on a freeway, smoothly and steadily driving into the future.

This entry was excerpted and adapted from Bennett’s essay “Why ‘Lost in Translation’ Is My Favorite Film of All Time.”