Chow Mo-wan files his nails, dons a dark jacket, combs his hair, and turns out the light. Maybe he’s going out for the night. Maybe he has a date.

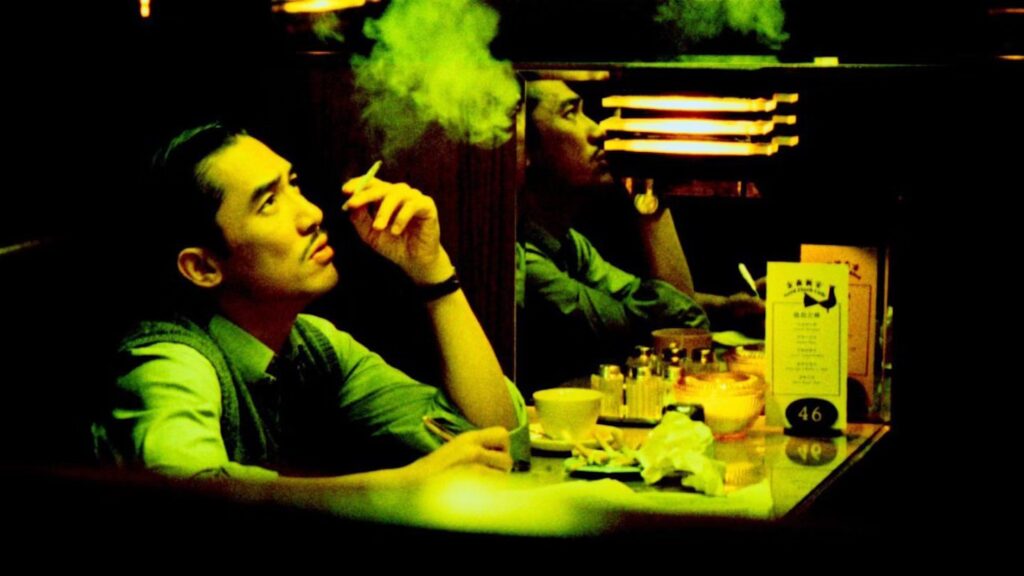

Embodied with sublime elegance by Tony Leung Chiu-wai, Chow cameos in the final scene of Wong Kar-wai’s “Days of Being Wild” (1990). It is the only time he shows up in “Days,” but the first of many appearances in Wong’s luxuriant tales of heartbreak in Hong Kong.

“A man like me has nothing much except free time,” Chow declares in “2046” (2004). “That’s why I need company.”

Over the course of three 1960’s-set films released over a period of 15 years, Chow searched futilely for enough company to fill his ample-yet-fleeting time. In “2046” (which is currently playing at Cinemagic), that search ends the only way that it can: in a flood of cathartic, ecstatic tears.

“Love is all a matter of timing,” Chow tells us. “It’s no good meeting the right person too soon or too late.” Life, for him, takes on a lonely logic—not only when he falls for a woman, but when he falls for Hong Kong itself.

At the end of “In the Mood For Love” (2000), Chow began his self-imposed exile to Singapore, seeking geographical and spiritual distance from Su Li-zhen (Maggie Cheung Man-yuk), the married woman with whom he had a chaste but impassioned affair.

“In love, you can’t bring on a substitute,” Chow muses. Nevertheless, in “2046” he returns to Hong Kong and seduces countless Su Li-zhen substitutes, armed with newly ruthless cynicism and a rakish mustache.

“So people are just time-fillers to you?” Bai Ling (Zhang Ziyi), a sex worker, asks Chow. “I wouldn’t say that,” he replies. ”Other people can borrow my time too.” She is neither the first woman—nor the last—to whom he extends this policy.

In “In the Mood For Love,” Chow was so timid that his idea of a grand gesture was sharing an umbrella. That awkward act of chivalry is long forgotten in “2046,” which reveals a man so hardened by heartbreak that he treats women not only as conquests, but as commodities.

“I’d pay anything to be with you, every day,” Bai Ling tells Chow. “Retail is fine,” he says. “Wholesale is out of the question.”

If “2046” were overstocked with chauvinist manifestos, it would be nothing more than a misogynist’s lament. Yet Wong isn’t crying; he’s asking, who does a man become after his heart is shattered? And what emotional kintsugi might meld the pieces back together?

The answer arrives, quite literally, in the mail. While renting a room at the Oriental Hotel, Chow befriends Wang Jing-wen (Faye Wong), whose father has forbidden her to see her Japanese pen pal and lover (Takuya Kimura).

“If your friend wants to send you more letters and you don’t want your dad to know, tell him to send them to my room,” Chow offers. Dutifully, he passes the letters through the cracks of the hotel’s peeling, emerald-green walls, playing cupid with ulterior motives as obvious as they are hopeless.

“Feelings can creep up on you unawares,” Chow reflects as his crush on Wang intensifies. “I knew that. But did she?” Rather than a Casanova, Chow turns out to be a Cyrano, tending to the desires of every heart but his own.

For Wong Kar-wai, “2046” became a nexus of past and future yearnings. Chow’s longing for Wang recalls Leung and Faye Wong’s quirky courtship in “Chungking Express” (1994); Chow and Bai Ling’s dalliances preview Leung and Zhang’s unconsummated kinship in “The Grandmaster” (2013).

These echoes enrich “2046,” but they never overwhelm it. Incestuous, self-referential fantasias of auteurism hold no allure for Wong, who shows how the story of a man can become the story of a region.

It is no coincidence that the titles of two sci-fi stories Chow is writing for a newspaper, “2046” and “2047,” reference the period of time that was to have marked the end of China’s pledge to Hong Kong: “One country, two systems.”

That vow evaporated in 2020, when a new security law effectively ended Hong Kong’s autonomy 27 years early. This, along with calls for an independent investigation into police violence against pro-democracy protesters, has retroactively shrouded Wong’s film with a darkly prophetic aura.

“She likes it a lot,” Wang’s father (Wang Sum) remarks after his daughter reads one of Chow’s stories. “But she finds the ending too sad. She wonders if you can change it.” Many Hongkongers probably wondered the same after the 1997 handover, which saw China claim control of Hong Kong from the United Kingdom.

During the end credits of “2046,” we hear a scrap from a Margaret Thatcher speech: “Hong Kong will maintain its economic systems and way of life for 50 years.” Despite being set before the handover, the film is haunted by those empty words, which deepen the melancholy of Chow’s romantic misadventures.

Hongkongers have grimly joked that Hong Kong only truly existed for the 30 seconds between the fall of the Union Jack flag and the raising of the Chinese flag. So it is in “2046,” a film about a man who loves vanishing women in a vanishing city.

“Do you remember you asked me if there was anything I wouldn’t lend?” Chow asks Bai Ling. “I’ve given it a lot of thought and now I know there is one thing I’ll never lend to anyone.” The breaking of his heart is inevitable, just like the breaking of the many promises made to Hong Kong.

Born in Shanghai but raised in Hong Kong, Wong brought a unique perspective to “2046”: He is a child of two worlds, and of the movies. “The only hobby I had as a child was watching movies,” he told Bomb Magazine in 1998. Had he already begun to imagine how instrumental that hobby would be in preserving what would be lost?

The Hong Kong of Wong’s childhood may be history, but if nothing else, it is a history etched in each frame of “2046.” Like Chow Mo-wan and cinema itself, some places—and their citizens—have nothing much except time. That’s why they need us.